Jenny Hall

Verses from the Dhammapada 421

In a world that is constantly changing, as the Buddha taught, clinging attachment will lead to suffering. In this article Jenny Hall looks at how this clinging causes us to feel cut off from others.

“He is a Brahmin who has given up all possessions and clings to nothing.”

This verse points to ‘Grasping’, the ninth link in the 12 Linked Chain of Dependent Arising. It arises from the eighth link, ‘Craving’.

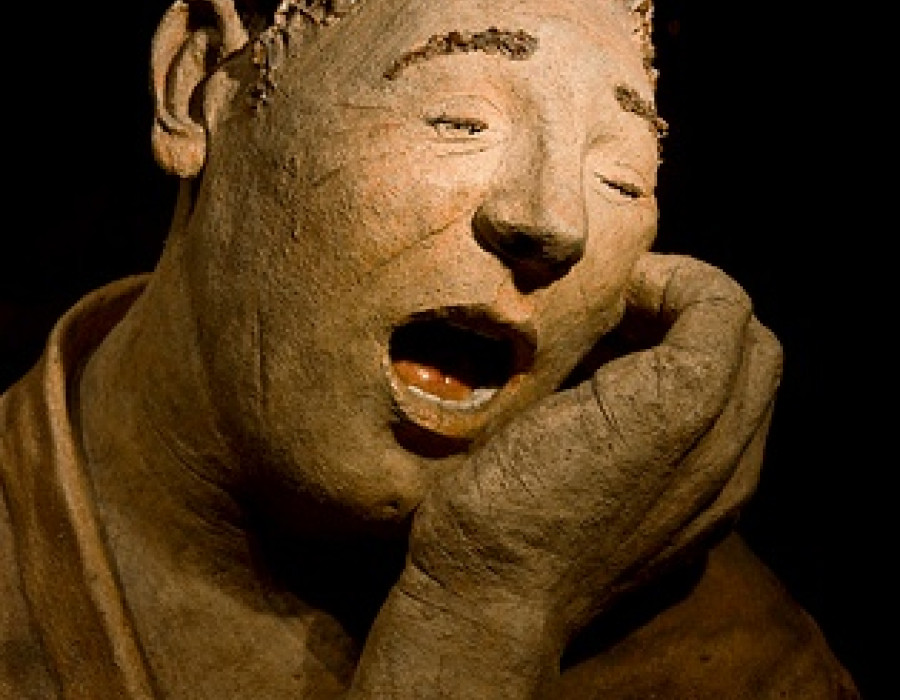

TV adverts attempt to convince us that the use of a certain shampoo will transform our hair to a dazzling silkiness. This will attract the partner of our dreams who will whisk us off to eternal happiness. Although we may smile at such beliefs, reflection reveals we invest certain objects with the ability to ward off our deep-seated fear of being ‘nobody’. We cling to our appearance, possessions, relationships, activities and beliefs. These attachments make up ‘me’.

As we age, there is often an attachment to appearing youthful. A few years ago irritation arose when a neighbour offered to carry my heavy shopping bags to my door. I told her I had extra to buy because my mother was ill and unable to shop for herself. I felt she was adding insult to injury when she responded with, ‘Good gracious! Is your mother still alive?’ Instead of being grateful for my neighbour’s helping hand, I was thoroughly disgruntled. However, it wasn’t actually her kindness that I objected to, it was the thoughts and ideas associated with it. It demonstrated to me the way in which attachments exaggerate everything.

After the encounter with my neighbour, further thoughts arose of bolstering my self-esteem by taking steps to make myself look more youthful. Should I buy some more fashionable clothes, or dye my hair?

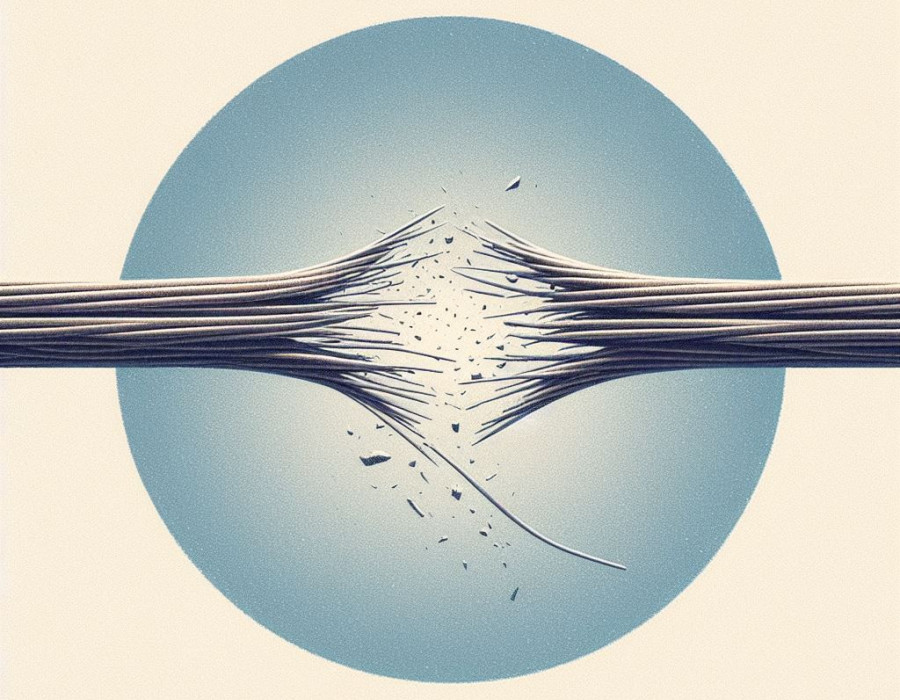

It isn’t so much the new item of clothing or hair colour that we find alluring, but our unrealistic expectations about what these items can do for us. There is a deeper clinging to a false sense of self. The Buddha taught that this clinging is the cause of all our unease. Nothing stays the same. It doesn’t matter how tightly we attempt to hold on, inevitably, whatever we cling to will be taken away. The new piece of clothing will wear out. The hair dye will fade. In fear we then desperately seek another talisman.

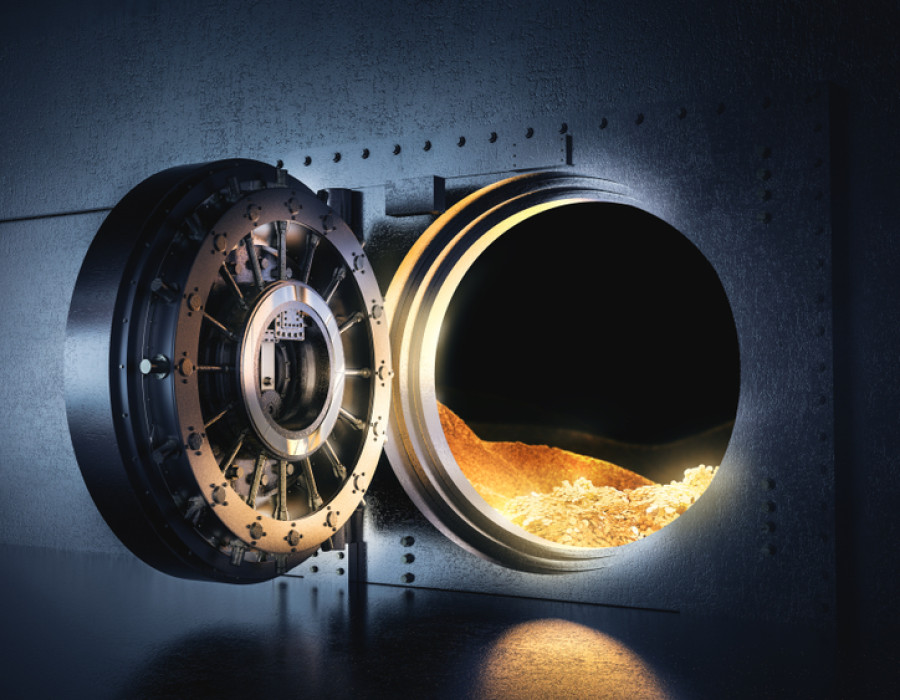

A prince and princess consulted a wise man. They said they wanted a talisman that would not only protect them from all disappointment but would also secure eternal happiness. He instructed them to go on a journey to find a truly contented married couple. They were told to ask such a couple for a small piece of fine linen worn next to their skin. This would be the magic talisman that they longed for. With great enthusiasm the prince and princess rode off. They soon arrived at a castle owned by a knight and his wife. The knight said they were happy, but not completely so, as they had no children. Next they came to a city where a burgher and his wife lived. They said they were happy except they had too many children. Finally they met a shepherd living in a field with his family. They were all dressed in rags. The shepherd said he couldn’t be happier. The prince and princess eagerly asked him for a piece of linen. The shepherd replied that he didn’t own a single thread. Sadly, empty handed, the prince and princess returned home. The wise man asked them whether they’d learned anything. The prince said: ‘Contentment is rare.’ The princess said: ‘It comes from within.’ The wise man smiled and said: ‘In your heart you have found the true talisman.’

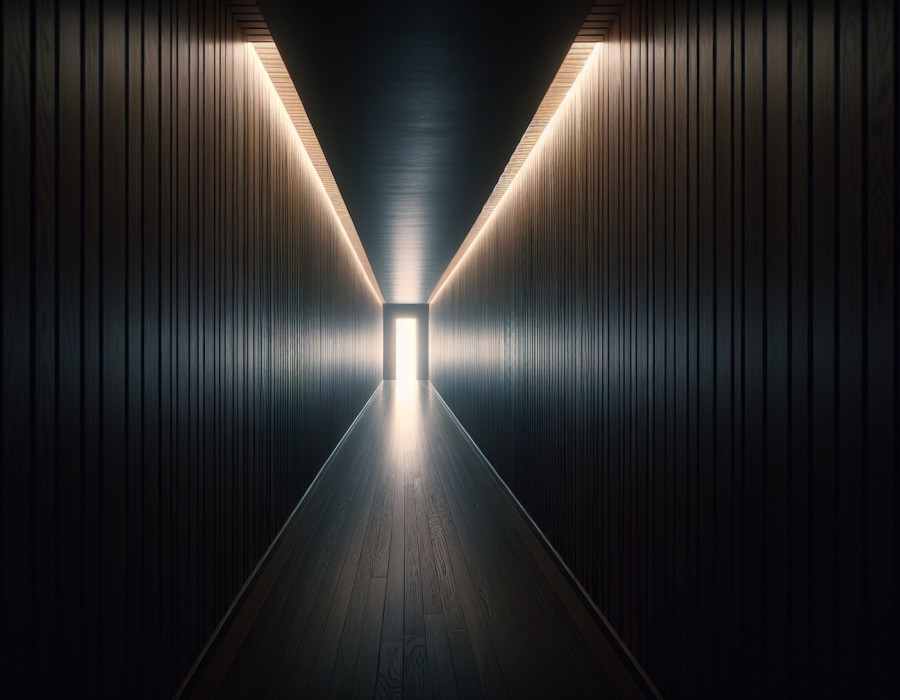

When we ignore the heat of desire behind our attachment, we browse online or flick through the Argos catalogue. Like the prince and princess we seek the talisman. When we meet the emotional energy and allow its churning, burning heat to burn ‘me’ away, then it is transformed into the strength and clarity of ‘Choiceless Awareness’. The empty heart is at one with all.

Even the thought of being ‘empty’ has to be dropped.

Master Joshu loved plants and flowers. One of his monks spent many hours growing and nurturing two bonsai trees. When they had matured, the monk decided to give them to Master Joshu. He bowed deeply and presented the trees to him. Master Joshu saw that the monk was still attached to phenomena. His heart was still not empty, so he shouted out: ‘Drop it!’

The monk obeyed and immediately let go of one of them. The pot smashed on the ground. Once again Joshu shouted: ‘Drop it!’ and the monk let go of the other pot, which, like the first, smashed on the ground. A third time the master shouted ‘Drop it!’ The astonished monk replied: ‘But Master, I have nothing left to drop!’ Joshu smiled and said: ‘Then take it away.’

When all thoughts are abandoned, then ‘I’ and all attachments dissolve. Then it is seen that everything is in a state of flux, ‘coming to be and ceasing to be.’ There is nothing to cling to and no one to cling.

Text copyright to Jenny Hall