Jenny Hall

Verses from the Dhammapada 360

Given that ’I’ (the ego) am the one who seeks to assert control over myself and ‘my’ environment, and ‘I’ (the ego) am the one who must be let go of, what did the Buddha mean when he says we must control the senses.

©

© Shutterstock

‘Control of the eye is good, and it is good to control the ear…’

We are bombarded by the media with endless enticing images and exhortations to ‘Look at this. Look at that. Get it now!’ There was once an advert showing a young woman gazing at a box of chocolates. She flitted from one to another murmuring ‘Oh choices, choices!’ We tend to treat life as a box of chocolates. Like the young woman, we are constantly ‘picking and choosing’. The Buddha taught that ‘I’ am made up of this picking and choosing, driven by hate and desire.

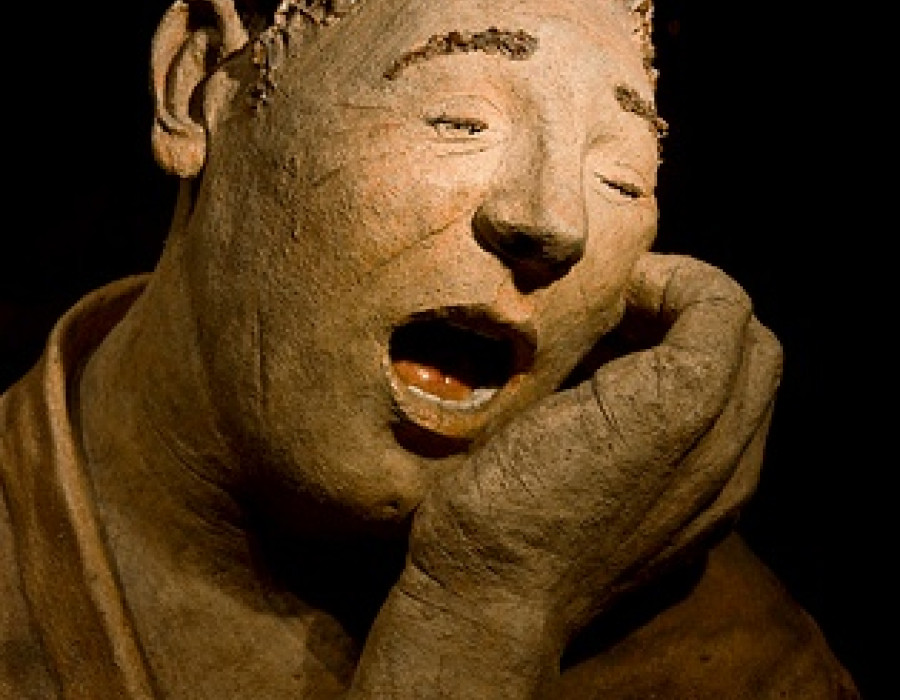

King Pygmalion nursed a deep hatred of all women. He boosted his own sense of importance by either ignoring or ridiculing them. Pygmalion was also a talented sculptor. He carved fine statues from ivory and marble. However, he had never created a female form. One day, the goddess Venus heard him complaining about women. She decided to teach him a lesson. The next morning a tall, mysterious stranger wearing a hood knocked on the door. The stranger greeted Pygmalion. She told him that the King of Crete was holding a contest. A laurel wreath would be awarded for the most outstanding piece of sculpture entered. There was only one rule. The sculpture must be that of a female. Pygmalion, very reluctantly, selected some marble. He proceeded to carve a beautiful woman. He worked all day until she was completed. That night he was unable to free his mind from the exquisite form he had carved. He rose from his bed. He sat gazing at her until daybreak. In the morning he was reluctant to submit her for the competition. Instead, he set her on a plinth. He named her Galatea. For a whole week Pygmalion refused to eat or drink. He was completely obsessed with Galatea. Finally, white as a sheet, Pygmalion dragged himself up the mountain to the Temple of Venus. He fell on his knees. He confessed that he had fallen hopelessly in love with a statue. He begged Venus to take away his pain. Returning to his studio he closed his eyes and rested against the door. When he opened them, he saw that the statue of Galatea had disappeared. A beautiful woman was standing in the shadows. She said ‘my name is Galatea’ and then disappeared. As she vanished Pygmalion’s heart lightened.

Like Pygmalion when we hate an object (person or situation), we attempt to push it away. When we desire it, we reach out and then cling, just as Pygmalion became attached to the statue. We fail to recognise its transience. We don’t see clearly because, like Pygmalion, we make images of reality. Taking control of the eye and ear means to empty these images out. This allows the senses to perceive reality as it really is. Each sense has its own consciousness. It is not ‘my’ consciousness. It is desire and hate and all the images they create that cloud the perfect clarity of seeing and hearing. All these must be laid down as Pygmalion bowed down to Venus. His suffering was relieved when the image of Galatea disappeared. When ‘I’ am emptied out the clarity of the senses perceives without obscurity.

After giving himself wholeheartedly into looking at a flower the Buddha held, Mahakasyapa became one with it. After wholeheartedly giving himself into sweeping a path, Kyogen became one with the sound of a pebble hitting a bamboo. The ‘I’ was emptied out. The flower and the sound of the pebble were reflected in the empty heart. There was no distinction between ‘I’ and ‘other’. There was non-duality, selfless awareness opens.

With the sight and hearing cleared, what has been previously ignored or taken for granted is seen and heard as if for the first time. Everything becomes significant. Ordinary everyday objects reveal previously unnoticed nuances. In Vermeer’s beautiful picture ‘Woman holding a Balance’, he is pointing to this serene communion.

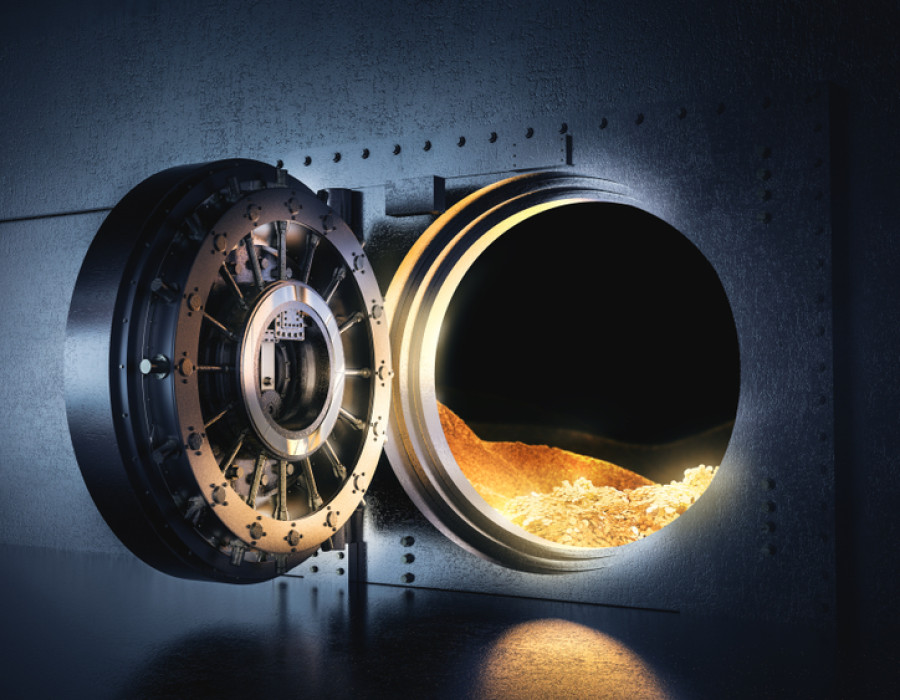

With appreciation comes contentment. It is seen that all we need is here in abundance. In gratitude objects are handled with care and compassion.

We make sure they are wholeheartedly arranged in their appropriate place. Venerable Myokyo-ni would spend time allowing a new object to reveal where it wished to be placed. As we continue to give ourselves wholeheartedly into the daily timetable, such warmth and intimacy prevails. Whether listening to a friend or ironing a shirt, we refrain from constantly checking our phone. In turn, our friend’s voice and the shirt relieve us of ‘me’. All sights and sounds offer this freedom. As Master Dōgen says:

‘To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things. To be enlightened by all things is to remove the barrier between self and other.’