Jenny Hall

Verses from the Dhammapada 366

A key element of a Zen monk's life is frugality and the avoidance of waste. Jenny Hall looks at the importance of this in a Buddhist practice to generate compassion and carefulness.

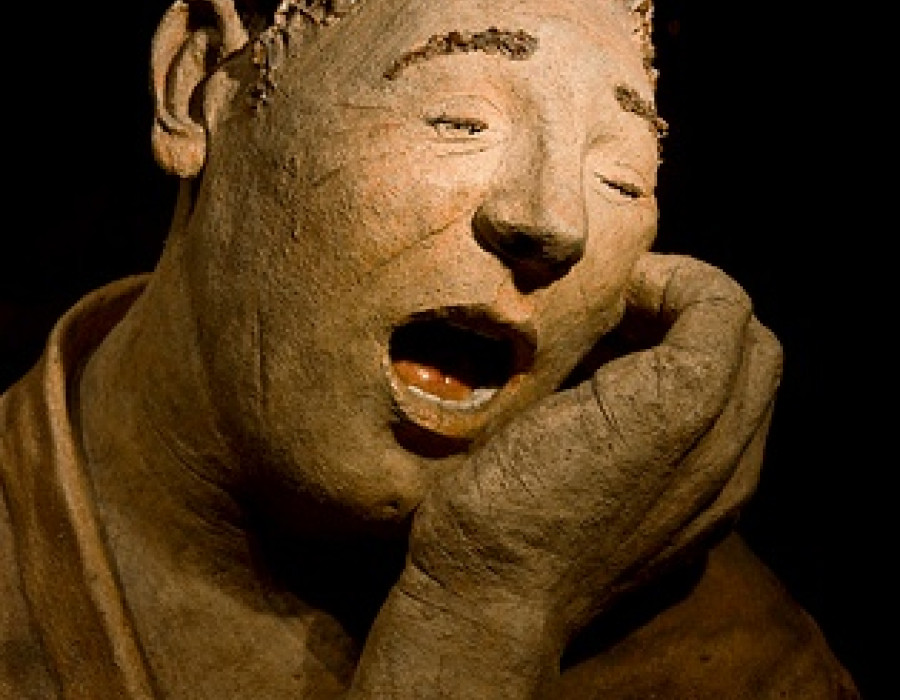

Sweeping monk… by Andy Serrano

Even though he has little but uses it wisely, the Bhikkhu will be praised if he lives an energetic life.

Even though he has little but uses it wisely…

When Soko Morinaga began his training under Zuigan Goto Roshi, he was assigned the task of tidying the temple garden. When he had swept up the leaves, he asked the Roshi ‘‘Where shall I throw the rubbish?’’ The answer came back “There is no rubbish!” Zuigan Roshi then proceeded to diligently sort through the mixture of leaves, stones , moss and earth. The leaves were used to heat the bath water, the stones were arranged under the eaves where dripping water created indentations in the gravel paths,the scraps of moss and earth were used to fill in the areas where shoes had scraped the moss off the rocks in the moss garden. Finally Roshi turned to Soko saying: “From the beginning in both people and things there is no such thing as rubbish.” In these words he was expressing the compassionate wisdom of the Buddha Nature. It also points to the ethical precept against stealing.

We may congratulate ourselves that we’ve never actually robbed anyone. However, in our ‘throw away’ society resources from the environment are constantly being ‘stolen’. Huge amounts of so- called waste are sent to landfill. We buy more food than we can eat. We leave lights on and devices ‘on charge’. It is common to wear a piece of clothing only a few times before discarding it. We take up more than our fair share. We also treat things without care or respect.

During the start of the COVID 19 pandemic, kitchen towel and cleaning wipes were in short supply. It was soon realised how extravagant and careless I had been in their use. Rather than throwing away an old t-shirt it was seen to be an excellent substitute. Made into a number of cloths such things could be washed and reused.

Desire, a passion the Buddha spoke of, not only drives us to ‘steal’ but also to laziness. We desire an easy life. Everything being in a state of flux, as the Buddha also taught, there is a time when possessions require repairing. In our busy lives we may plead there is no time or we have no energy for this. Before the COVID 19 crisis we would perhaps pop down to Argos or browse online for replacements. With many such avenues closed to us during lock down, valuable opportunities have arisen for giving ourselves reverently into the desire which drives such actions. Instead of wasting the precious energy in thought streams and trips to the shopping mall, we learn to say ‘‘Yes’’. We invite the hot flames to burn ‘me’ away. The energy is then transformed into the clear seeing of the Buddha nature rather than the seeing from ‘my’ way only that suits me. The needs of everything are seen. Appropriate action is taken. Everything is helped to its proper place and function.

… the Bhikkhu will be praised if he lives an energetic life.’

Rather than judging ‘self-isolation’ at home as a problem, gratitude grows for the opportunity for living this energetic life as we give ourselves wholeheartedly into the daily routine of making and washing a floor cloth or polishing the door handles. Such repeated actions provide teaching analogies.

When we first moved into our flat, the door handles were ingrained with dirt. The first reaction was that ‘these need changing’. It is this feeling of dissatisfaction with life generally that often propels us into the Zen training. We want something new. Then the idea of trying to clean the handles arose. When we started to rub them with brass cleaner, the dirt seemed to increase! In the training we are taught to stay with things as they are. When we look inwards we seem to be getting worse. It takes a lot of hard work to keep polishing and polishing. Gradually the shining brass is revealed. In the training we give ourselves wholeheartedly over and over again to what is being done.

These are glimpses of the Buddha Nature.

At last the door handles are restored to their original glory. However, if we neglect them by failing to continue to regularly polish, they start to darken again. In the same way, after years of training we begin for longer periods to live in what Krishnamurti called ‘choiceless awareness’, the Buddha Nature.The training never ceases. If we become negligent, we begin to fill up with thoughts of ‘me’ and ‘mine’ once again.

When we diligently continue to polish we joyfully and gratefully realise that everything around us is offering the opportunity to us to give ourselves wholeheartedly away. When we polish the door handles we are polishing our heart. When ‘I’ am emptied out there is at-one-ment with the situation. There is nothing to strive for because nothing is lacking.

…