Jenny Hall

Verses from the Dhammapada 31

The persistence of the natural world is a good example of how awareness and attention are a natural function of the Buddha-Heart.

“The bhikkhu who avoids negligence and is ever watchful advances like a fire, burning his fetters.”

“The bhikkhu who avoids negligence …”

A young journalist reported that she decided to abandon her smartphone for a few days. Initially, she felt completely lost without it. Then she began to notice people around her in the street, and became fascinated by the different styles of architecture she passed on her way to work. She said she hadn’t realised she had been neglecting the awareness of her environment to such an extent. It is easy to ignore the daily routine. We tend to label it ‘boring’, and attempt to distance ourselves in myriad ways. We fail to ‘take care’ of whatever is arising from moment to moment.

“ … and is ever watchful …”

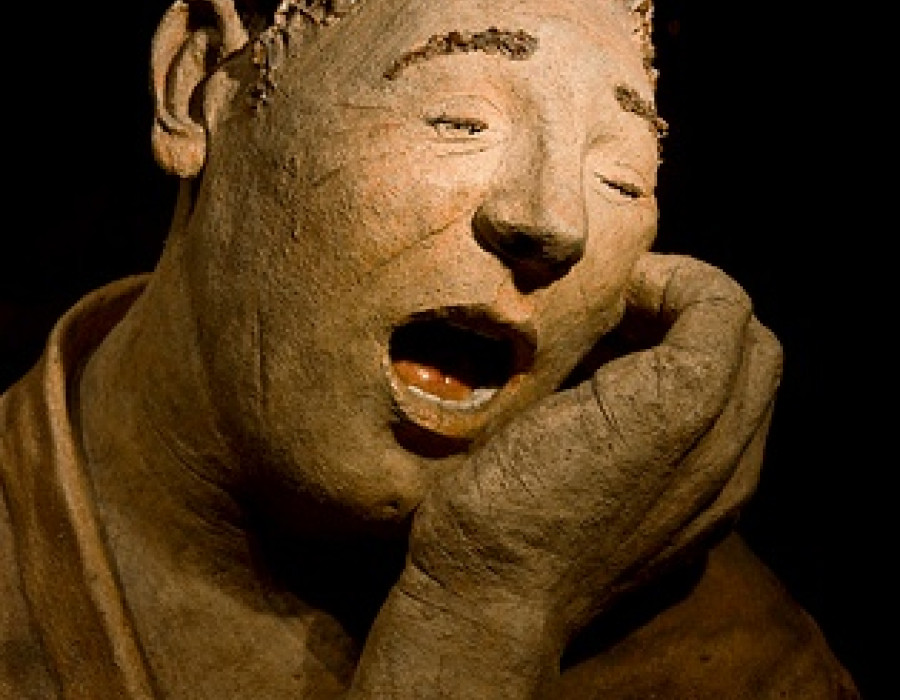

This past autumn, a little robin alighted on the garden wall and watched the leaves being swept up. Upright and alert, his image is seen everywhere as the festive season approaches. He is a symbol of goodwill, helpful friendliness – the very opposite of negligence. Unlike the robin, we neglect our posture regularly. We are not ‘watchful’. We repress feelings of boredom and antipathy, and so neglect precious opportunities for their transformation into warm friendship with everything we encounter.

“ … advances like a fire, burning his fetters.”

An Inuit man and his son tended a fire just outside their igloo, and never allowed it to go out. While the father hunted the great white bear, his son looked after the fire. The bear hated the pair, and used his cunning to hide from them. He knew that the fire was precious, and believed that if he stamped it out, father and son would fall into a deep sleep and never awaken again.

The bear waited for his chance – and one day, it came. The father had fallen ill, and was unable to go hunting; his son continued to add sticks to the fire, as he had been taught. By the second day, he began to feel hungry. He was also afraid, as he could hear the bear prowling around the igloo at night. On the third day, his father couldn’t move, and the boy was finding it very difficult to keep his eyes open. He threw a few more sticks onto the fire. Eventually, however, he fell asleep. Immediately, the bear pounced on the fire and stamped it out. The igloo became colder and colder. Father and son were soon encased in frost and snow.

The boy, however, had been friendly with a little robin. When the bird flew into the igloo to warn him that the fire had gone out, he discovered that he couldn’t rouse him. The robin found a little spark amongst the ashes. He flapped his wings so hard that a flame slowly appeared and ignited a twig. The fire grew hotter and hotter. It blazed up and scorched the robin’s breast feathers, which turned red. Suddenly, the boy woke up, and rushed to pile more sticks onto the fire. He didn’t notice the little robin fly away.

The father recovered, and the great white bear slunk away. When the robin visited the igloo again, the boy noticed the little bird now had a red breast – but he never understood why.

Like the robin fanning the flames and suffering their heat, so does Zen training involve giving ourselves to the hot emotional energy driving our thoughts, and transforming it into the warmth and goodwill of the open Heart.

If we attempt to repress the passions, like the great white bear stamping out the fire, we lose contact with this precious energy. We become ‘cold’, like the Inuit father and son. We ‘fall asleep’ in the dream of ‘I’.

Shunryu Suzuki said: “When you do something, you should burn yourself completely, like a good bonfire – leaving no trace of yourself.”

We become bored with our everyday routine because we don’t ‘burn’ ourselves completely. We remain attached, saying “I have done this”, or “I’m only prepared to do that”. When our partner spills juice on the freshly cleaned kitchen floor, we complain: “I’ve just done that!” Clearing litter from our own close, we resist picking it up in town, saying: “I’ve done quite enough already.” These are the fetters that haven’t been destroyed, and which imprison us.

A man called Kichibei had a wife who had been ill for two years. Kichibei swept the floors, cooked the meals and washed the clothes. A neighbour remarked that it must be very tiring for him. He replied: “No, I’m never tired. Looking after my wife is both a first and last experience.” Kichibei lived completely in each moment.

When we are also burned away in each moment, the Heart opens. Goodwill extends to all, like a robin’s song.

© Jenny Hall