Jenny Hall

Verses from the Dhammapada 134

Emptiness was described by the Indian sage Nagajuna as the True Nature of phenomena. It's realisation forms the central insight in Mahayana Buddhism. Jenny Hall explores our fear of emptiness and sees the way as going right through this fear.

.jpg)

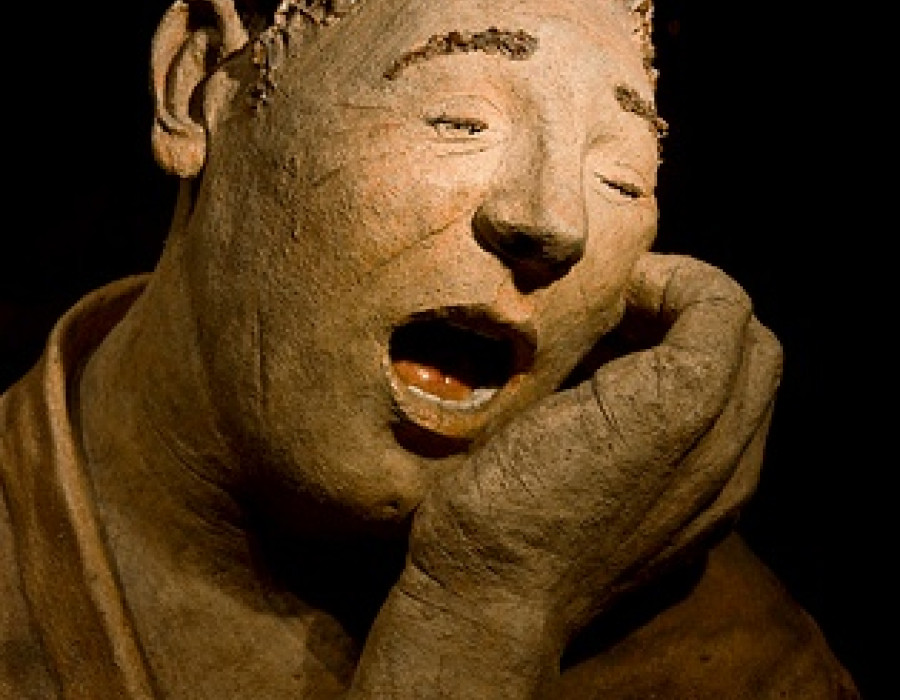

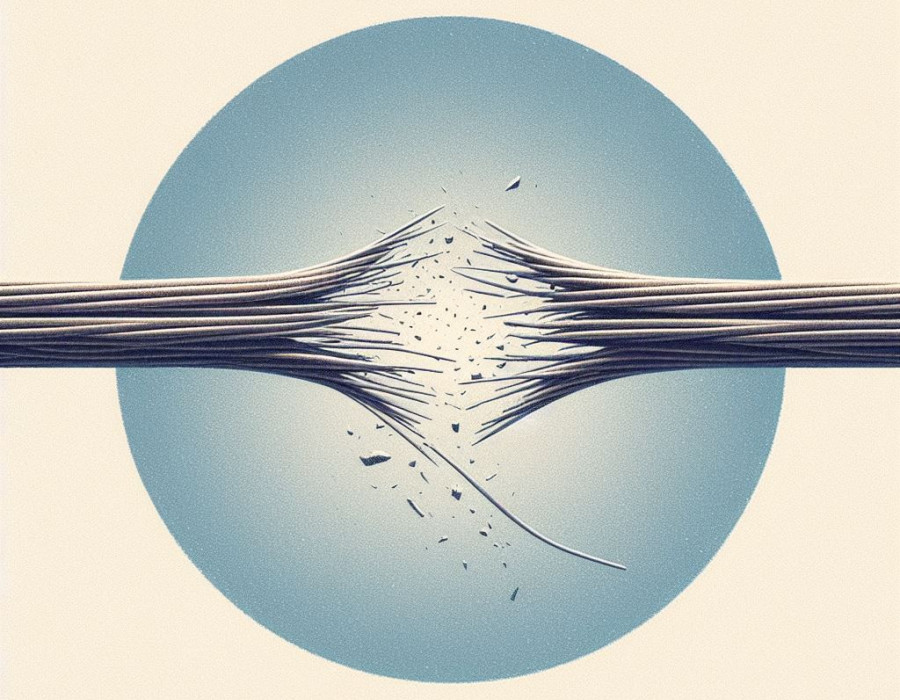

“He who is silent like a broken gong has reached Nirvana; there is no quarrelling in him.”

This verse points to sunyata, which means, broadly, ‘emptiness’.

“He who is silent like a broken gong …”

In our culture, when we say we feel ‘empty’, we usually judge this as a negative state – of boredom, or futility. Venerable Myokyo-ni would frequently instruct us to just sit quietly in an armchair. In doing so, there is the opportunity to recognise the fear of being ‘empty’. Very soon, we become restless. We attempt to fill the space, turning on the news or checking our emails.

When I was a child, my grandfather had a marionette show. Among the puppets was the figure of an old woman. Her capacious skirt was made up of numerous pockets, each containing a miniature doll. The show also included a stilt walker, a grinning clown and a drunken policeman holding a bottle of beer.

Like the hidden dolls in the old woman’s skirt, secreted away in our heads are memories of the past and plans for the future. Like the puppet strutting around on stilts, we chase after possessions in the attempt to make ourselves ‘bigger’. Perhaps we adopt certain personae such as the clown, to become more popular.

There was also a Scaramouche in the show, which appeared to be decapitated at first; without warning, my grandfather would twitch a string, and the head would suddenly appear. I found it terrifying. Similarly, we allow our own ‘heads’ to perpetuate fear and suffering. Like the drunken policeman’s perceptions, befuddled by beer, so the ‘stories’ we tell ourselves distort reality and beget confused views that lead, in turn, to harmful action.

“… has reached Nirvana …”

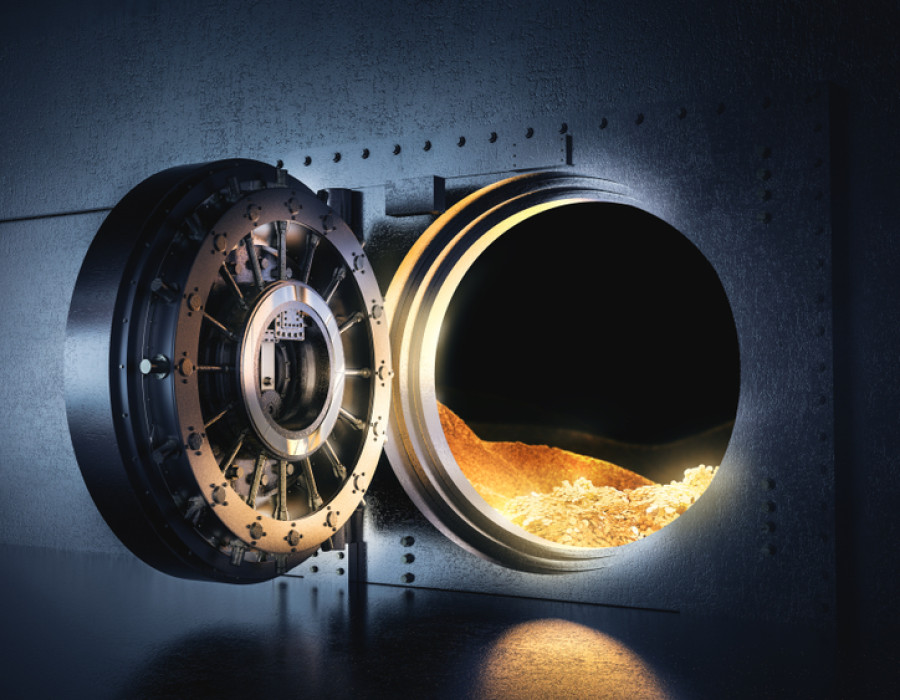

It is the fear of emptiness that creates such confusion. Through Zen training, we are led to recognise and embrace the desire to be someone, which masks the fear of being no one. We are encouraged to meet, head-on, the raw emotion that drives us. Daily life practice involves giving ourselves away, over and over again, into the fiery energy of fear, whilst maintaining our course through the training. ‘Nirvana’ means ‘extinguished’. When craving has burned the ‘I’ away, emptiness opens, a vast, spacious awareness: Buddha Nature. In this openness, everything is completely free from my preconceptions. When even the idea of ‘empty’ is emptied out, then reality is seen clearly – and all action is appropriate and helpful to every being.

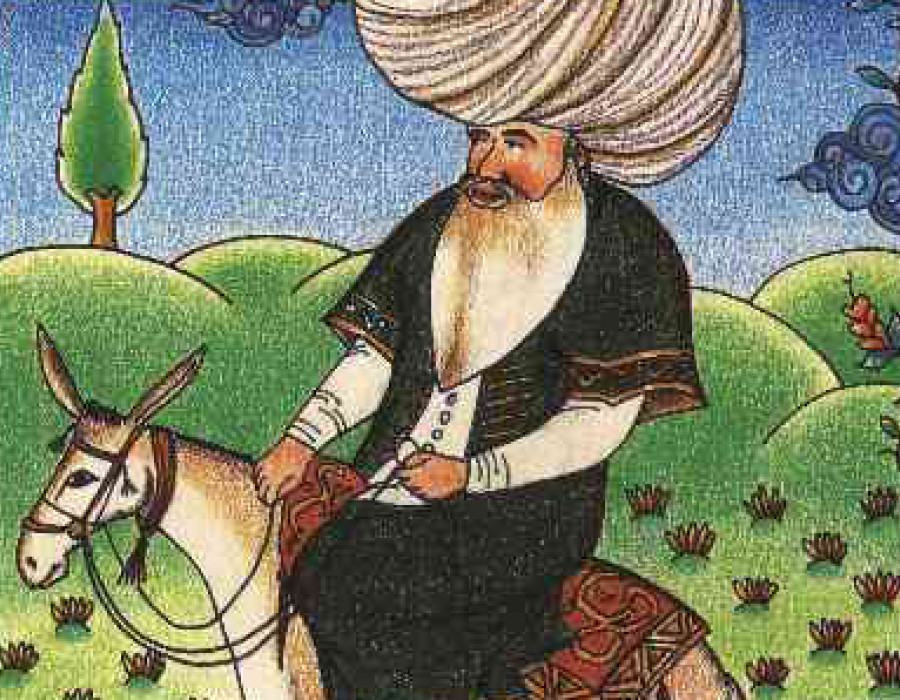

In a village near Master Hakuin’s temple lived an old woman who ran a teashop. She was a tea master and, reputedly, a Zen master as well. One day, Hakuin’s students decided to visit the shop to find out if the old woman really was a Zen master. However, she was able to discern whether or not a visitor was coming to her with an open heart, to learn the Way of Tea, or with a heart that was intent on verifying her understanding of Zen. The sincere, open-hearted visitor would be served tea gracefully; the visitor who was just testing her would be beaten with a poker. When Master Hakuin’s students returned, sore and bruised, he told them they were lucky to have been allowed to leave in one piece.

‘… there is no quarrelling in him.’

The Chinese character for ‘heart’ has a large empty space at its core. For the heart doesn’t need to be active – it just needs to be spacious, with no ‘I’ to judge any person, situation or object as an ‘enemy’. There is no ‘quarrelling’, only natural friendliness, warmth and gratitude, flowing with everything as it comes to be and ceases to be. We no longer feel separate.

Hans Christian Andersen’s story “The Teapot” points to this transformation, when ‘I’ am emptied out. A very vain teapot felt superior to all the other crockery in the kitchen. It was always boasting of its spout and handle. One day, it was dropped, and the spout and handle fell off; the tea leaves and boiling water emptied out onto the floor. The following day, it was given away to an old woman. It was desolate. Yet it wasn’t long before the old woman planted a flower bulb in the broken teapot, and the bulb sprouted into a beautiful flower. The teapot completely forgot itself as the flower was enjoyed by all.

Te Shan said: “Only when you have no thing in your mind and no mind in things, are you vacant and spiritual, empty and marvellous.”

© Jenny Hall