Jenny Hall

Verses from The Dhammapada 286

While doubt is seen as one of five hindrances to meditation, ‘the great ball of doubt’ is one of the three requirements for Zen training. What is this ball of doubt and how can we develop it?

©

© Shutterstock

‘Here I will pass winter and summer’ ,so the fool reflects not realising the dangers to his life.

The verse points to the importance of doubting ‘me’ and my intentions in the Zen training.

The Buddha taught that everything is impermanent and constantly changing. This fact consoles us when trouble comes, and it distresses us when we lose something we cherish or identify with. In such a situation we desperately cling to what is basically ephemeral. In this way suffering is created. The Buddha also taught that the ‘I’ is a delusion.

This delusion attempts to secure itself against inevitable change by making plans for the future. As the verse says, we say ‘Here I will pass winter and summer’.

Many years ago, recently married friends made a list of all their future years together. They added what they wanted to obtain and achieve at the end of each one. In hindsight many of these ambitions failed to materialise. Those that did, failed to satisfy for long.

It is in such circumstances that what the Zen tradition calls The Great Ball of Doubt may arise. It arises when something we have planned or relied upon disappears or is seen as empty.

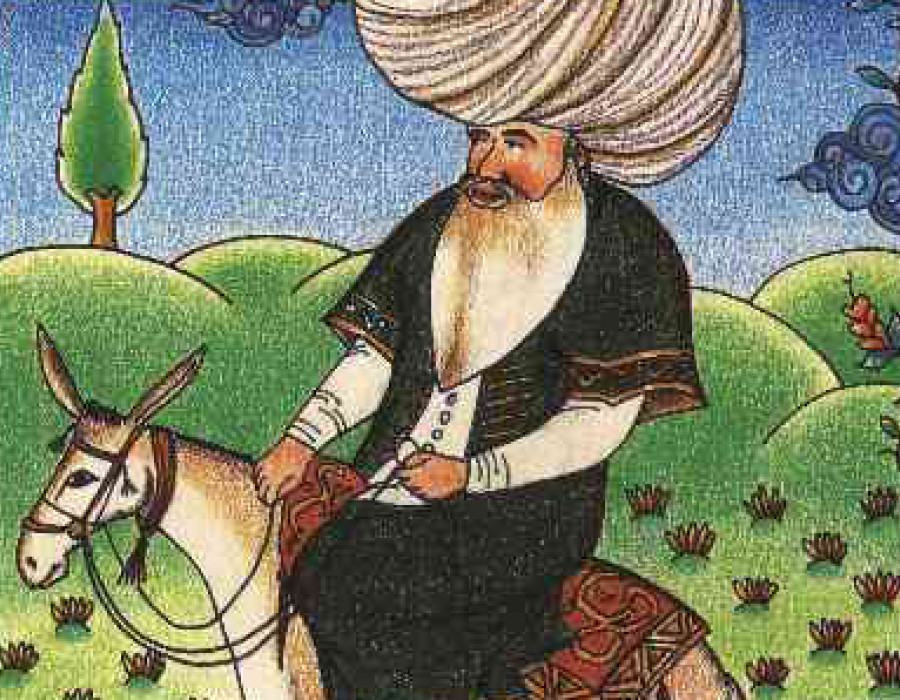

When he made the three [AC1] trips from the palace, the Buddha suddenly came face to face with old age, sickness and death; for the first time he doubted his comfortable life. This doubt was the impetus behind his search for enlightenment. It led eventually to the discovery of the way out of suffering.

In Katherine Mansfield’s story The Garden Party , a young girl called Laura is filled with excitement as the family prepare for the party. They are very welloff, living in a large mansion set in beautiful grounds. On the fringes of the estate is a huddle of ramshackle overcrowded cottages. Laura is discouraged by her parents from socialising with the poverty stricken labourers and their families who live there. In contrast her life is filled with ease and delight. On the morning of the party, the rooms are filling up with exquisite lilies and the tables with delicious food. Suddenly bad news arrives. One of the labourers has been killed in an accident. Laura’s charmed life is unexpectedly touched by tragedy. As the verse expresses it, she glimpses ‘the dangers ‘ to this life. The doubt arises in her heart that they should allow the party to continue. However, when she shares this doubt with her family, they are adamant that it must go on.

Perhaps to make amends in the evening, Laura’s mother insists that Laura takes the remainder of the party food to the grieving family. Once again, Laura doubts that this is appropriate. She obeys. The encounter with the corpse fills her with reverence and awe.

Whispers of doubt often arise when we, like Laura’s mother, attempt to stifle feelings of unease with ‘good intentions’. The word ‘doubt’ comes from the Latin word ‘dubitare’, meaning ‘to hesitate’. We hesitate because we don’t know which way to go. Such a situation arose just before embarking on the Zen training.

The houses surrounding us became dwellings of multiple occupancy which were rented by a stream of noisy tenants. My husband’s fragile health prevented us from moving. I began to doubt my ability to cope.

When we start the Zen training, rather than trying to solve problems we are encouraged just to look. The problems are seen as precious training opportunities. Doubt in ‘I’ is important. We are gradually helped to realise that it is nothing more than a thought stream. We are shown how to meet the underlying desire, anger and fear that drive these thoughts. When we invite the emotional energy to burn ‘me’ away, the Buddha nature is revealed. In the clear seeing of this spacious awareness, reality is seen from moment to moment totally free from ‘me’.

Eventually it was seen that the noise in our flat came and went. It was constantly changing. ‘I’ had been making it into a solid, permanent phenomenon by mulling over yesterday’s noise and worrying about tomorow’s. By wholeheartedly giving myself into the hot, surging energy when the noise did arise, ‘choiceless awareness’ opened up. There was no ‘me’ to suffer. There was acceptance. It was seen that with so many tenants crowded together in such small spaces the disturbance was unavoidable. Compassion and warmth flowed. After some time, the tenants moved out. As the Buddha taught, the situation changed. Our flat became peaceful.

During the Zen training, glimpses of ‘choiceless awareness’ help perpetuate the doubt that the delusion of ‘me’ is capable of seeing reality clearly. This doubt spurs on - wholeheartedly giving myself into whatever is arising whether emotion or situation. Even if we have been training for many years if we cling to the idea that there is anything to attain for ‘me’, ‘I’ am still here. The sight is still not clear. So once more, ‘I’ wholeheartedly give myself into the moment , again and again and again.