Jenny Hall

Verses from The Dhammapada 24

Having to do work that we don’t like can leave us feeling drained and fatigued. Zen training teaches us how to reclaim that energy.

.jpg) ©

© shutterstock

“An energetic man who is considerate in action will increase in reputation”.

This verse could be seen as pointing to Right Livelihood, one of the steps of the Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path.

The Buddhist tradition encourages employment that benefits the world and its inhabitants. At least it encourages work which creates minimal harm. ‘Livelihood’ comes from the Old English word ‘līflād’ meaning ‘way of life’. Therefore, it can be seen as much broader than earning one’s living.

It involves the whole of our existence. Included in it are numerous actions and everyday tasks such as washing, cleaning and cooking etc.

‘Right’ Livelihood means a ‘selfless’ way of life. The Buddha taught that the ‘I’ is a delusion. It is deluded because it is made up of constant thought streams driven by desire and hate. These thought streams obscure the clear perception of reality. The ‘I’ is confused most of the time. It has little connection with what is actually occurring from moment to moment. It cannot help but cause harm. The practice of Right Livelihood therefore involves wholeheartedly giving ourselves away into whatever is being done.

“An energetic man… “

When ‘I’ am emptied out, the sight clears and becomes ‘choiceless awareness’. This is the ‘energetic man’. Being the life force, it is expressed in boundless energy which far exceeds what ‘I’ can muster.

We often waste this precious energy. We fritter it away in complaints that life is becoming more and more stressful. We often tell ourselves that we have too much to do and too little energy to do it.

Visitors to a monastery were usually asked to help sweep the grounds. These grounds were extensive. A new arrival watching one of the monks sweeping asked him ‘Do we have to sweep all of this?’ The monk smiled and said, “No, just what’s in front of your broom”. All we have to do is to give ourselves wholeheartedly to what is being done in each moment.

Repetitious actions offer valuable training opportunities. They are a useful means of discerning how often we resist giving ourselves and attempt to escape into thought.

As a student, in the vacations it was necessary to supplement my grant by working at a variety of jobs. One was in a cake making factory. From 8:30am in the morning till 5:30pm in the afternoon we had to fill cake tins moving on a conveyor belt. Cake mixture continuously flowed from a shute. Judging the work as ‘boring’ I often sought relief in day dreams. The result was that some containers were missed and the mixture ended up on the floor.

“… who is considerate in action…”

When daydreams are emptied out, choiceless awareness is ‘considerate in action’ because it sees clearly what is required and always acts appropriately. This is the opposite to the karma producing action of ‘I’ which is blinkered and motivated by what ‘I’ want, not what is needed for the common good.

The common good includes the welfare of all objects. There is a story about a monk who was clearing up. He threw away the two used matches left on the altar. Ajahn Maha Boowa asked the monk what had happened to them? The monk replied that, as they were used up, he had thrown them away. Ajahn Maha Boowa pointed out to the monk that he always used partially burnt matches to transfer the flame from one candle to another. He wouldn’t throw a match away until it was completely burnt out.

Caring for utensils in this way also benefits the people we live and work with. After washing up, we wholeheartedly wipe the sink clean. We wholeheartedly squeeze the sponge dry. We wholeheartedly hang the tea towel on its hook. The kitchen is kept serene and tidy. The harmony of our surroundings is safe guarded.

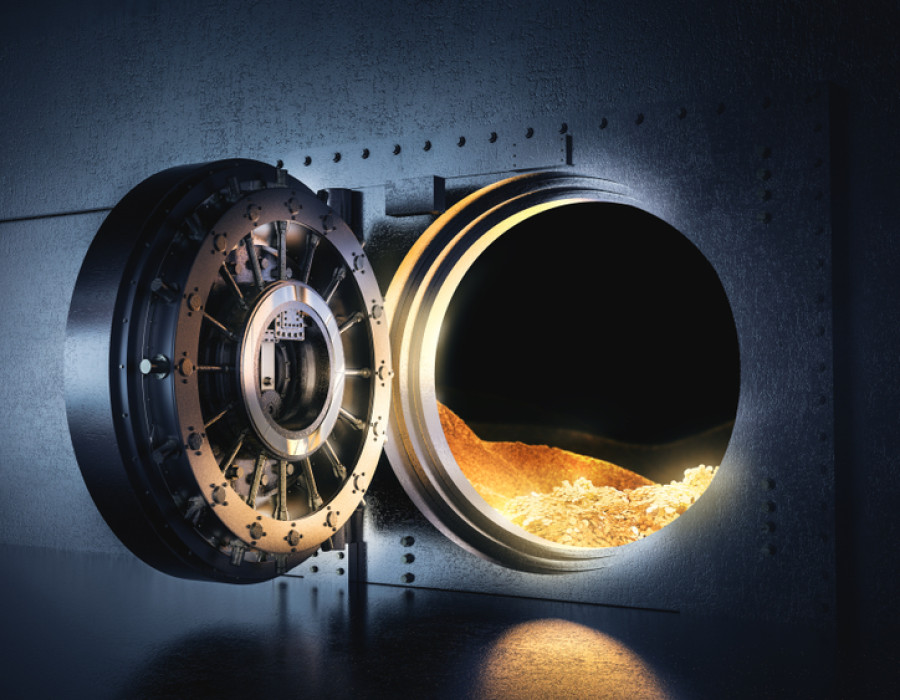

“… will increase in reputation”.

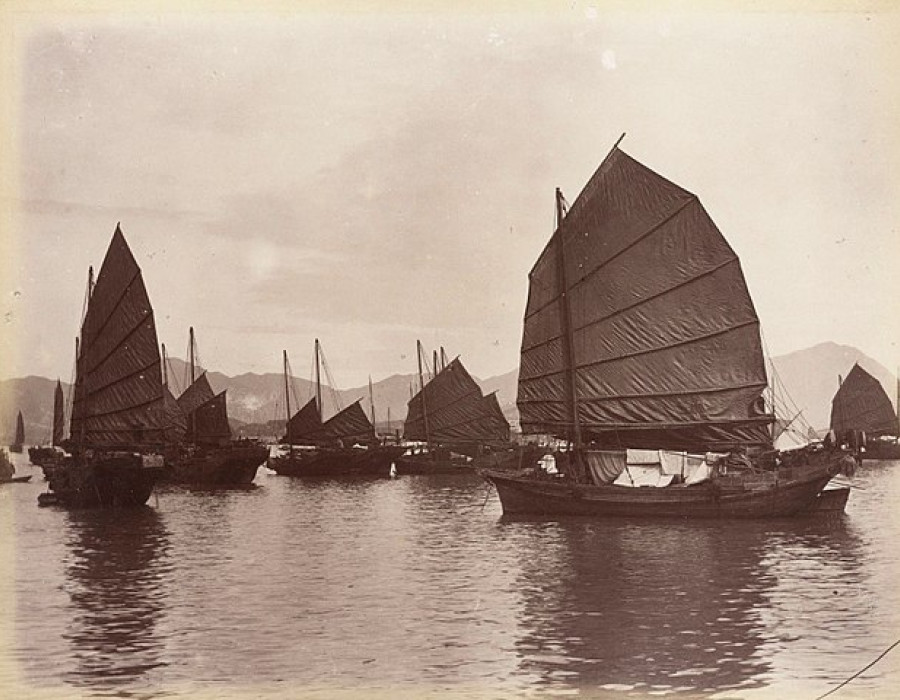

The Sung Dynasty pottery of China is renowned for its exquisite decoration. It would be easy to assume that all the Sung potters were consummate artists. In fact, in Tz’uchou, young boys were often given the task of decorating the pots. The majority came from poor families and were illiterate. They wouldn’t have been familiar with the Chinese characters included in the pictures. The elegant use of the brush was the result of each child drawing the same picture hundreds of times each day. The movement would be executed quickly and unselfconsciously over and over again. The result were patterns of great beauty.

When all needs are met, everyone and everything is content. We could say that this is the meaning of ‘will increase in reputation’. When the great energy of choiceless awareness flows, sweeping, washing up and painting become art forms. Like a Chinese pot they become an expression of the graceful dance of life.