Jenny Hall

Dhammapada Verse 19

Verses from the Dhammapada

How can knowledge become an obstacle to awakening?

©

© Shutterstock

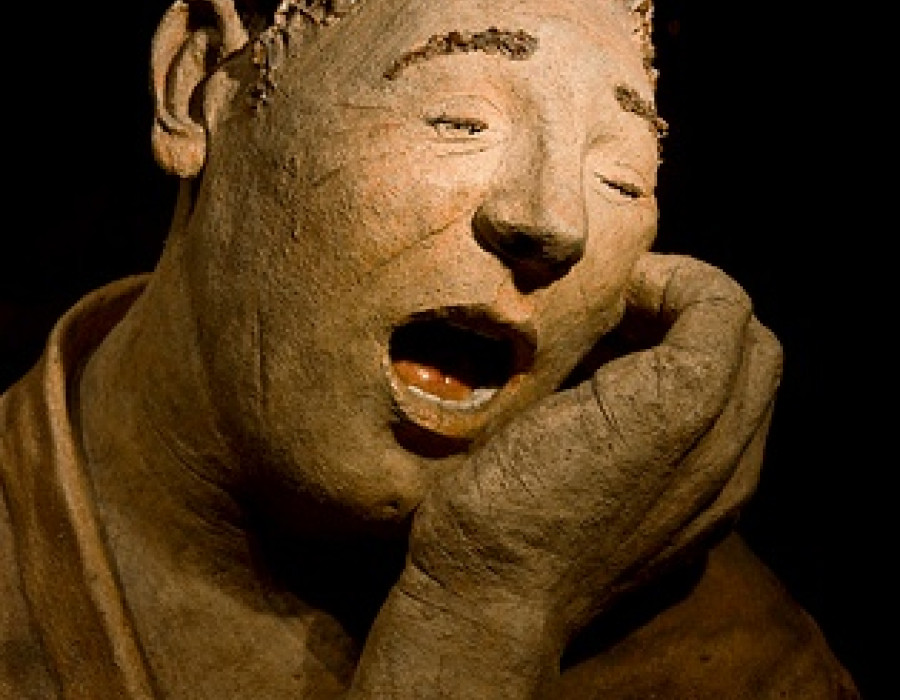

‘The man who talks much of the teaching but does not practice it himself is like a cowman counting other’s cattle’.

A politician once proclaimed ‘‘Education, education, education!” Education involves both teaching and learning. Those who have been taught may take great pride in the latter. This pride can often lead to clinging to ideas of how the world is.

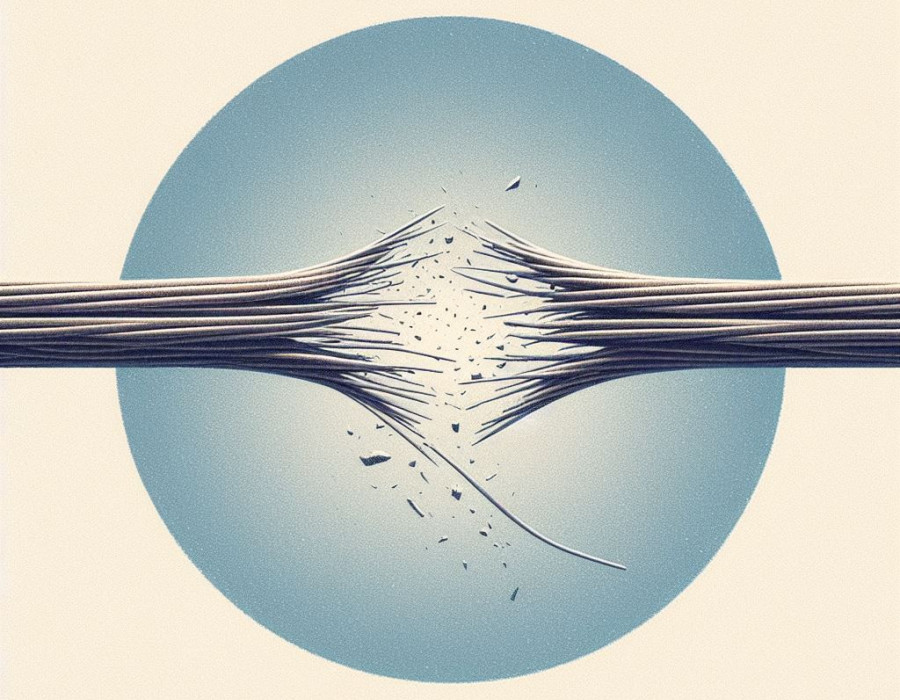

However, the Buddha pointed out that the world, ourselves included, is in a state of flux. Truth cannot be fixed. It can only be seen when we are totally free of all ideation.

Every year a central heating engineer checks and overhauls our boiler. To do so it is necessary to dismantle the gas fire. Half way through the procedure last year there was a strong smell of gas. When it was pointed out to the engineer, he replied that it was nothing to be worried about. He said he had just cleared the pipes and, in his experience, this always leaves a smell of gas. Naturally, we accepted his professional judgement. Later in the day we returned from a walk. There was still a very strong smell of gas. Failing to make contact with the engineer, we called the Emergency Gas Leak Team. They confirmed there was a leak. One of the screws in the gas fire had not been secured. The original engineer was relying on knowledge he had accumulated. He didn’t respond to the moment. He later admitted he had assumed the screw was in place. He hadn’t actually looked.

Reality can only be seen when we are completely free from assumptions.

A student was talking to a Zen master about Zen. The master said ‘You have too much Zen!’ The student was mystified. He said ‘Why don’t you like me talking about Zen? Surely, it is only natural for a Zen student to talk about it’. The master replied ‘Because it turns my stomach’.

Trevor Leggett would often warn that all the Buddhist teachings, commentaries and stories are just fingers pointing to the moon.

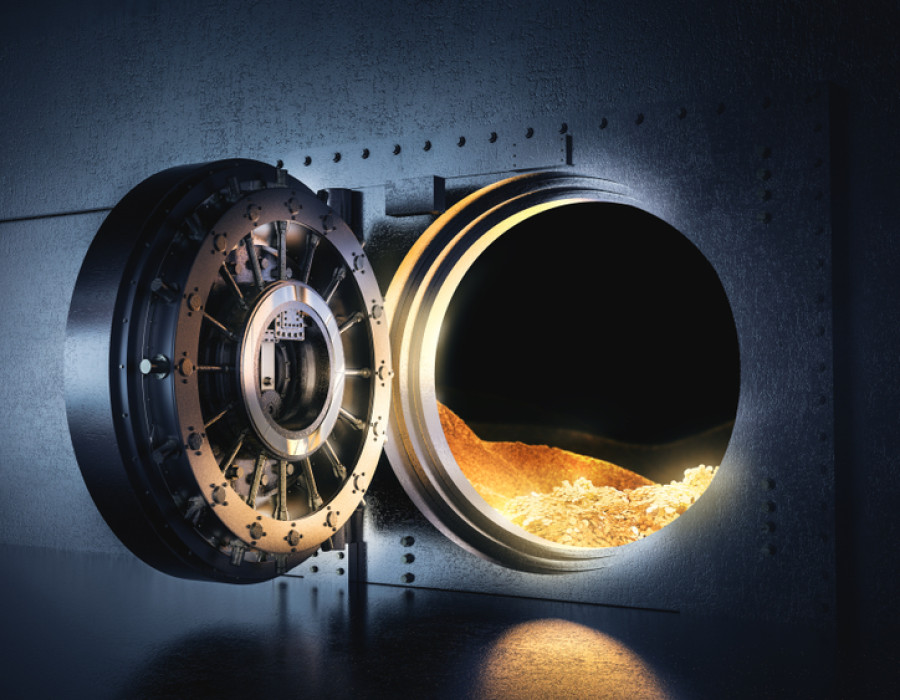

Zen Master Mu-nan had just one successor, called Shoju. One day Master Mu-nan called Shoju to his room. He told him that he was now very old and only Shoju would be able to carry on the teaching. He handed him a book and said, ‘This book has been handed down from master to master for many generations. I have also written my own commentaries added in the light of my own understanding.’ He said the book was very valuable. It was his wish to present it to Shoju. However, Shoju replied that if the book were so valuable, Mu-nan should keep it. He added ‘I received your Zen without writing’. Mu-nan said he understood but that he would like Shoju to keep the book as a symbol of the teaching. He pressed it into Shoju’s hands. They were standing near a brazier. Immediately Shoju threw the book onto the burning coals. Master Mu-nan shouted angrily ‘What are you doing?‘ Shoju retorted ‘What are you saying?

Ajahn Chah would often point out that there are many opportunities for reading about the Dhamma/Dharma. What is rare is taking the opportunity to read our own heart. When we stop and look, we find the unease and suffering that the Buddha spoke of. He said ‘Suffering I teach and the way out of suffering.’ He didn’t ask us to learn about suffering. He didn’t ask us to read about it or talk about it. He invited us to recognise it and to discover the way out of it for ourselves.

When we embark on the Zen training, we are encouraged to see for ourselves that the suffering within our own heart is caused by craving for and clinging to the ephemeral. We begin to discover the cauldron of hot emotional energy which in the Zen tradition is called the Bull. If thwarted in any way, it churns and burns. We are shown how to greet and suffer the flames. It is by directly allowing its turmoil that the wild energy is gentled and so transformed. The Buddha nature, or choiceless awareness, then opens. Knowledge, which makes up the idea of ‘me’, does not assuage suffering. This only ends when craving is allowed to burn ‘me ‘and all ‘my’ fears away. In that selflessness there is compassion, warmth and serenity.

When Ven. Myokyo-ni was asked what Zen Buddhists believed, she replied ‘We do a lot of bowing’. The ‘I’ is made up of ‘my learning’, my understanding’, what I know’. All this has to be laid down. What is important is ‘not knowing’.

An elderly friend who had been in the Zen training for many years, rarely planned. If he was asked about a future arrangement, his eyes would twinkle and he would say, ‘We’ll see!’