Jenny Hall

Verses from The Dhammapada 147

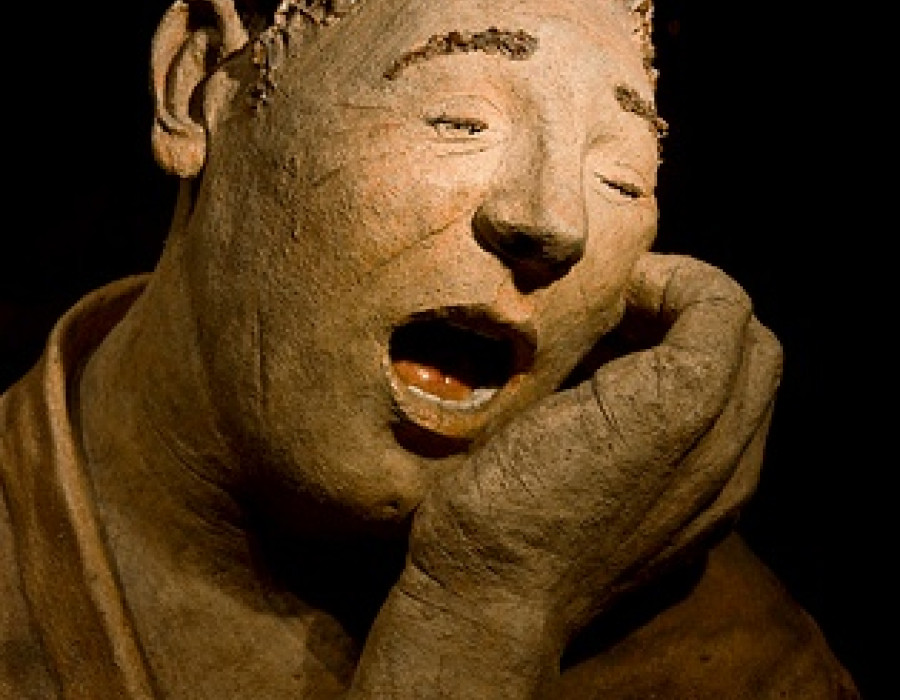

The Buddha said, ‘Look at the body, sickly racked with pain, which does not endure.’

Jenny Hall investigates...

©

© shutterstock

‘Look at the body, sickly racked with pain, which does not endure.’

‘Look at the body…’

There has been much discussion in the media concerning the increasing number of hours that people are spending in front of their screens. We are exhorted to abandon them for short periods in order to take some exercise in the fresh air. However, the ubiquitous mobile phone often means that we are not actually at one with our bodies as we do so. James Joyce wrote of one of his characters, “Mr Duffy lived a short distance from his body’’. Like him, we spend most of the time inour heads.

‘… sickly racked with pain…’

If we are lucky enough to enjoy good health, we perhaps take our body for granted. As we age and it becomes less reliable, it may become a source of anxiety. Recently it has been necessary to ban the use of botox by teenagers. It seems even the very young are taking steps to obliterate the signs of ageing. Initially the appearance of old age may come as a shock. My mother once asked a friend if she was pleased with her cataract operation. She replied; ‘No! When I first looked in the mirror, I burst into tears seeing all my wrinkles for the first time.’

Contemplating sickness and the transitory nature of the body and meeting the emotions that this evokes are opportunities for discovering the Buddhist path.

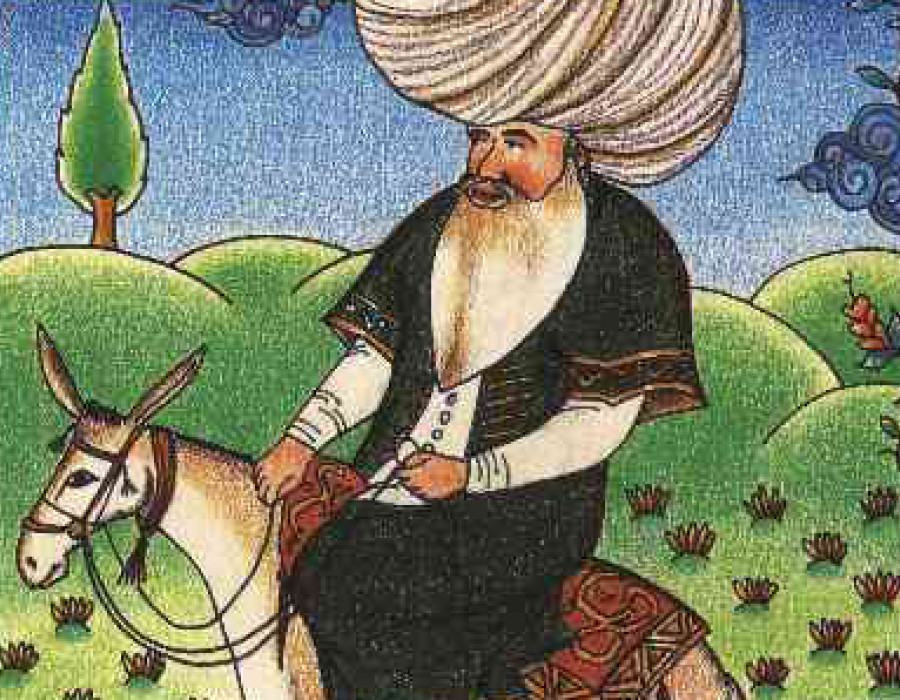

When the Buddha was born as Prince Siddhartha, a prophet predicted that he was destined to become either a world ruler or a great sage. His father the King encouraged the former. He gave his son every advantage, shielding him from the harsh realities of life. Despite living in luxury with a beautiful wife and child, Siddhartha felt discontented. He longed to explore the world beyond the palace walls. Finally, he managed to persuade his trusted charioteer to take him into the town. It was on four such excursions that he saw a beggar, an old cripple, a corpse and finally an ascetic sitting quietly by the roadside.

These were his first encounters with poverty, sickness, old age and death. Deeply disturbed by these sights, the ascetic’s serenity inspired Siddhartha’s own quest and eventual discovery that ‘within this fathom long body’, is found all of the teaching, is found suffering, the cause of suffering and the end of suffering.

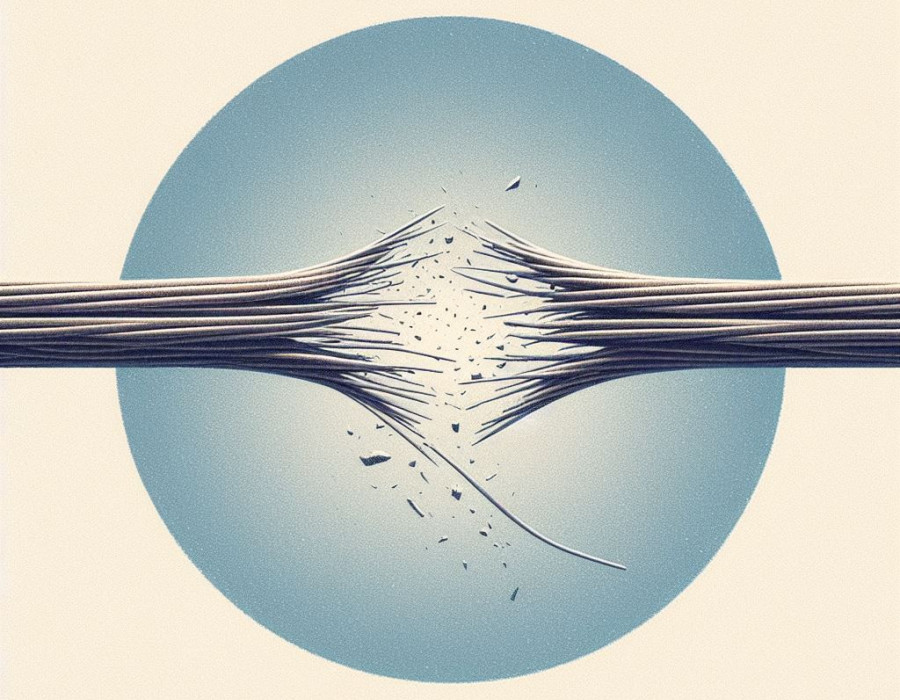

The Buddha in these words wasn’t promising the end of physical suffering. He didn’t say we would never experience pain. He was referring to the suffering of the heart. However, we are usually very reluctant to meet it. Venerable Myokyo-ni once said that it wasn’t the events of life that make us fearful but the emotions they engender. In the Zen training, these emotions are regarded as valuable training opportunities. Our teachers encourage us to dive right down into the place where they see the surge. When we invite the energy to burn ‘me’ away, ‘I’ drop off. The wisdom and compassion of the Buddha nature (Choiceless Awareness) open. There is at-one-ment with all. This includes physical pain. If it arises, there is no ‘me’ to name it.

When we become ill, we often try to take control by making pictures in our head. One way of doing this is to spend the time waiting for a doctor’s or hospital appointment researching diseases on the internet or in medical books. When my husband developed some unusual symptoms, using such information I tried to reassure him by suggesting they could be a manifestation of quite minor ailments. My husband told me to ‘stop fussing’; when I replied that I was only trying to help, he said ‘I can’t bear to see you looking so worried.’ I then realised it was actually my anxiety that I was attempting to quell. And all I was doing was increasing my husband’s.

As we waited for my husband’s MRI scan results, we just sat quietly together. The anxiety was met over and over again. On the way home my husband thanked me for all my help. I had, in fact, done nothing except meet the inner turmoil.

‘…which does not endure’

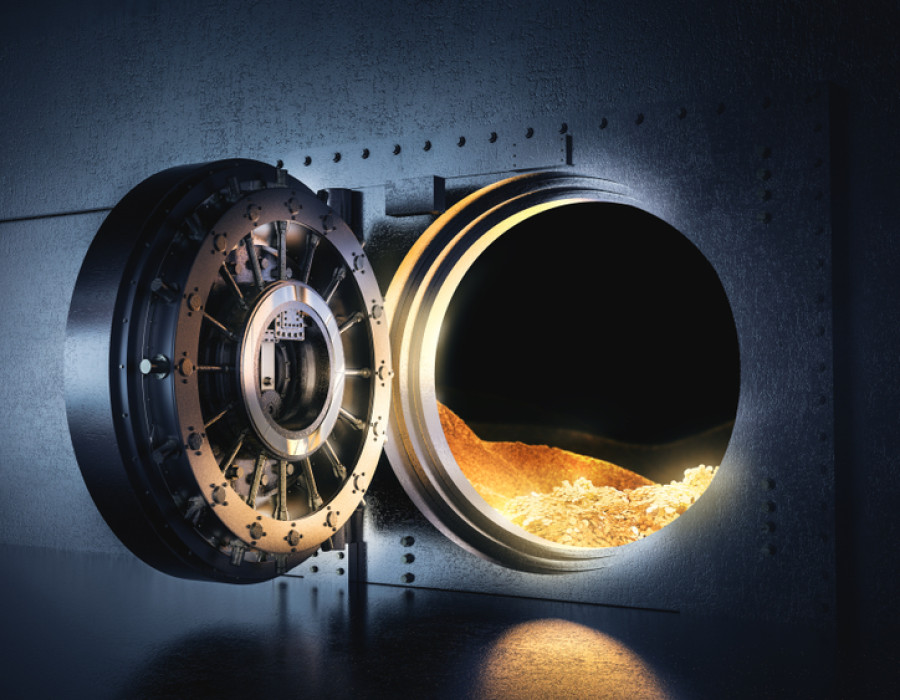

Old Master Bankei had a cook called Dairyo. Dairyo decided to give Master Bankei only fresh miso because of his advanced age. Made from wheat, soya beans and yeast the miso fermented very quickly. Master Bankei noticed that he was being served only fresh miso. He asked Dairyo for the meaning of such preferential treatment. Dairyo explained it was for his health and in deference to his age and position.

Bankei stopped eating.

He locked himself in his room for seven days. For seven days Dairyo sat outside the door asking his teacher’s pardon. There was no answer. Finally, another pupil called out to Master Bankei. ‘You may be alright but this young disciple can’t go without food forever. Bankei then opened the door. He smiled and said to Dairyo ‘I want you to remember this when you are a teacher. I insist on eating the same food as the least of my followers.’

The fermenting miso points to the transitory nature of all things, including the body, whether in sickness or in health. Master Bankei’s refusal of special treatment points to the detachment from position and from all ideas such as ‘being old’ or ‘being sick’. His insistence on eating the same sour miso as his pupils points to the at-one-ment with all, which comes about when all such ideas are emptied out.

Living in the clarity and awareness of the open heart, we are in accord with Ven Sariputta’s words;

‘My body and mind are not me,

Birth and death cannot touch me.

I smile.’