What Floats Your Vote?

Blog

What does Buddhism have to say about the world of political power and money?

©

© shutterstock

This is being written on 5th November, which in the United Kingdom is traditionally Bonfire Night. It can’t have escaped anyone’s attention that this year it has been overshadowed by a certain election going on across the Atlantic.

Given the apparent deep divide this election has stirred up, perhaps it is ironically apt that both share the same date.

Many years ago, at a Buddhist summer school, I recall someone, who was of vocal political opinion, telling me that he thought it impossible that one could be a Buddhist and not vote for the political party for which he voted. Even then, it was to my mind a case of God is on my side-ism which even we ‘enlightened’ Buddhists, it seems, can fall into.

These days, people are divided about mixing religion and politics, and given our past it is not difficult to see why. Anyone with knowledge of British history will know just how bloody that could be during, for example, our own Reformation and across the channel in continental Europe they didn’t do much better. So, with the Renaissance and birth of the European Enlightenment, we learned that it is best by and large to keep our religious views private. In a society where there are many denominations, discretion becomes the better part of valour, enabling peace around the dining table. Of course, it is not the same everywhere and on the whole the U.S. has no such reticence about mixing the two. However, this article is not about this question; rather I would like to look at how Buddhism might inform us as to how to see the world of political power and money. I include the latter as it usually does accompany the former and it would be naive to ignore it.

The starting point for our contemplation is a story associated with Master Obaku. He was a disciple and a Dharma heir of Master Hyakujo, who was a great reformer and instituted the monastic rule in China. It is he who is said to have coined the saying, “A day without work is a day without food”.

Obaku, in turn, also had his own Dharma heirs, the most famous being Rinzai Gigen Zenji, the founder of the Rinzai Zen School.

Obaku, as abbot of a great monastery was also teacher to the Chinese Emperor. One day, Obaku was invited to accompany the Emperor to the banks of the Yellow River to see the many trading ships that sailed up and down to the many ports along the shore, a sign of just how well the Emperor was managing the country and the economy. A good trading economy is a sign of political stability which in turn suggests law and order.

In the same way, the United States has played the ‘World Policeman’ since the end of WWII with the establishment of the Bretton Woods system. Undeniably, this has brought trading stability and has also meant that the United States would secure trade routes around the world. So indeed the Emperor could also boast that he too had created the conditions for wealth and security for his people.

In his joy, the Emperor exhorted the Master to gaze upon the myriad ships that were sailing by. Obaku is said to have replied tersely that he saw only two ships! The Emperor was taken aback and replied that there were far more than two ships before them - just look! But the Master was adamant there were only two ships. When the Emperor voiced his displeasure at the Master’s obvious contrariness and demanded an explanation, Obaku replied that the only two ships he could see before him were the Ship of Gain and the Ship of Fame. The story continues that the Emperor, who deeply respected the Master’s wisdom, pondered the point. In time, he brought in a number of reforms that brought even greater stability and happiness to the Empire.

So, what do we make of Obaku’s point and how is this relevant to us in our times? I think there is a question here that Obaku is asking. Who does this serve? It might also be voiced as - what does this serve? These are not the same question, but both are relevant.

The Ship of Gain is wealth and the Ship of Fame is status - he who has status also wields power. So, we have with these two both money and political power. The question Obaku, I believe, asks is do these serve something else or are they ends in themselves? These are two very different ways of framing a world reality.

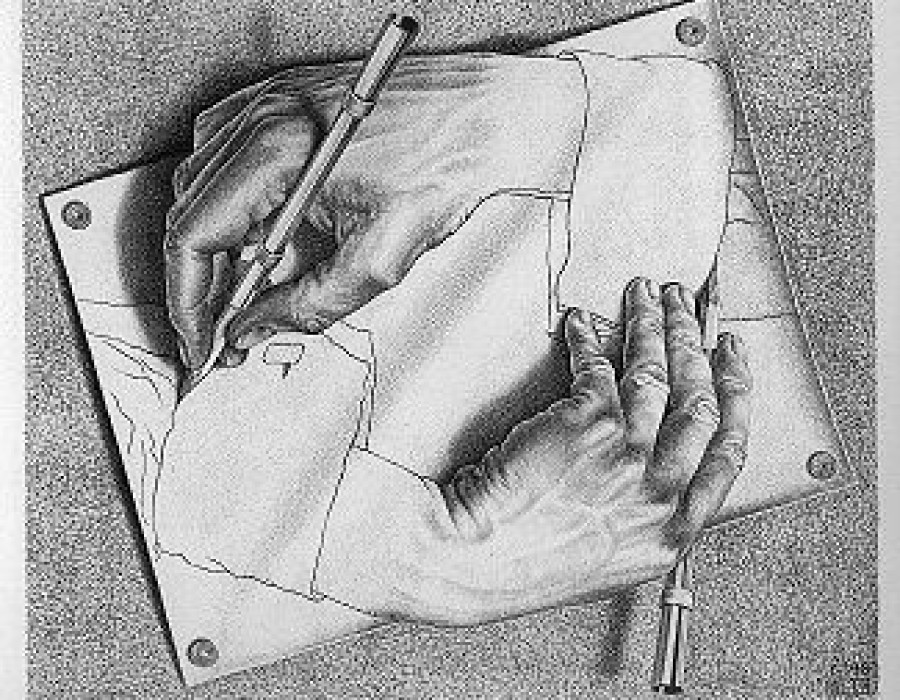

Even the most unworldly person, whilst in a material body, cannot ignore either money or status. They are simply part and parcel of the human world. Even the ascetic Gautama realised that he would starve to death if he didn’t eat something and rejected this as a spiritual path. In the early Sangha he forbade the monastics from handling gold and silver. In this way he made them totally dependent upon the laity whom they were to serve. If they failed to fulfil this task, then the laity could withhold goods and money and thus had the power to force them to reform or disband. The Sangha had the status but the laity the money. This was the Buddha’s way of providing a check on the seductive power of status. It is this seductive power of money and status to which Obaku points with his two ships.

As long as these two ships are in service, then, like a fire that is well-contained, they can provide light to see by, heat to cook by, and warmth to sit beside and enjoy good times with others. However, if we feed the fires irresponsibly, then the danger is that all goes out of control and then shows a destructive face.

If these two serve only themselves, then what has been accumulated suffers the fear of loss. This quickly becomes a zero-sum game and it doesn’t take long for paranoia to take hold.

When the contract between wealth and power and that which it is supposed to serve is broken then the different sides become self-serving. The other side is demonised and one’s own faults ignored. A fragile equilibrium is in danger of being overturned.

It may be that this is just the nature of impermanence being worked out. We suffer the consequences of our success in banishing this awareness of our fragility. Thus, our hubris grows and we forget the network of vital relations upon which that success depends.

There is an old Breton fisherman’s prayer that goes:

“O Lord, the sea is so vast and my boat is so small”.

It was inscribed on a plaque by Admiral Hyman Rickover and given to President John F. Kennedy who had it mounted on the wall of the Oval Office.

The blessing of this prayer is in the remembrance it evokes of our fragility in the vastness of the world and how much better off we are when we serve each other.

The Zen Gateway Blog

Dharma, Culture, Philosophy & Life-ways