Dragon Slaying: A Policy For Disaster?

Blog

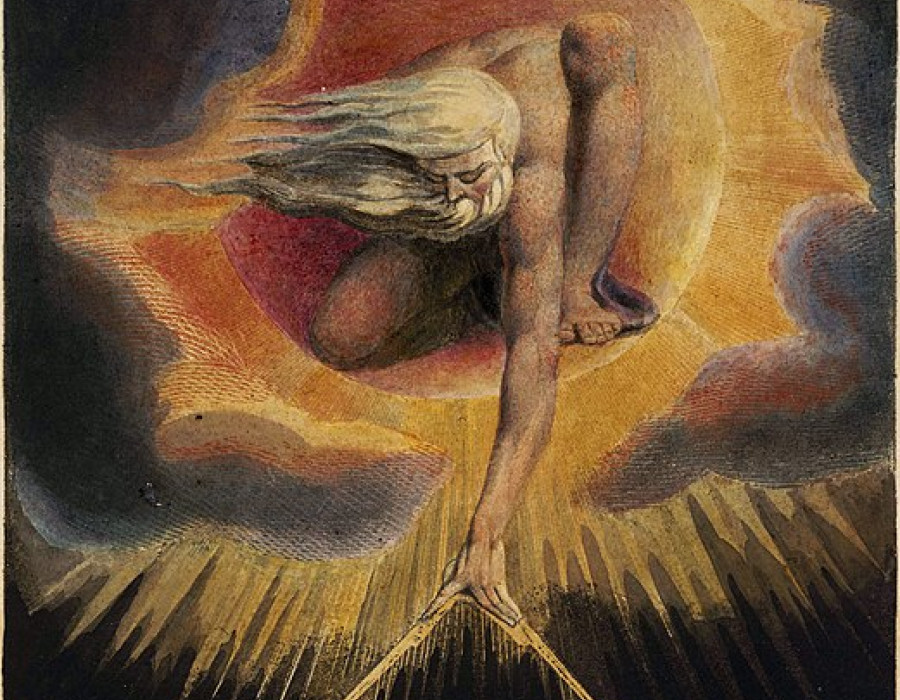

Martin Goodson examines how the myths that have shaped our culture are molding our perceptions of the crises we face today.

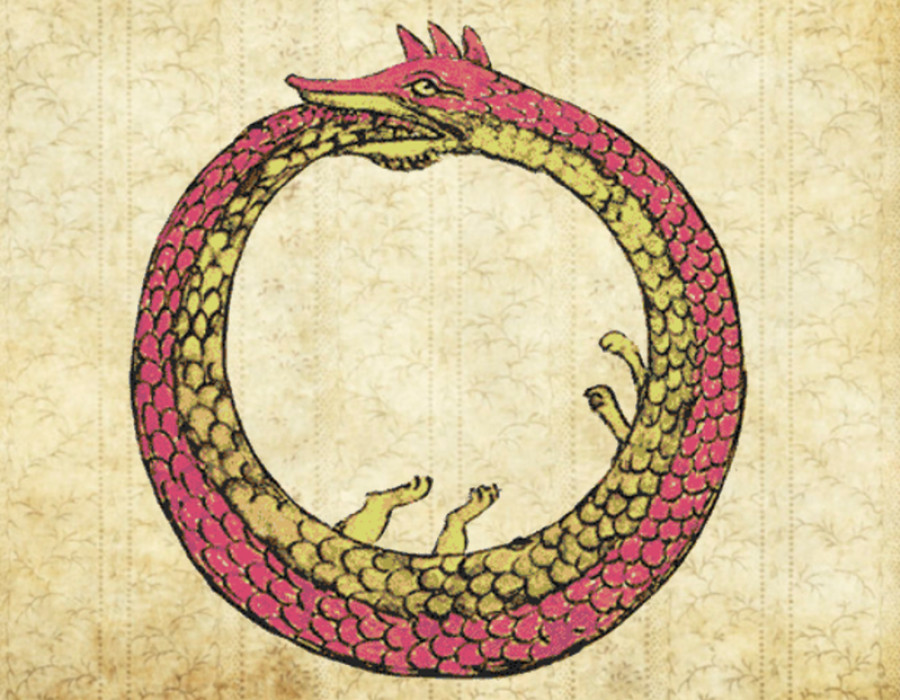

Ouroboros drawing from a late medieval Byzantine Greek alchemical manuscript.

graphics by Dominic Kearne

The killing of MP Sir David Amess is the latest in a long line of shocking events in the U.K. These events in turn drive a continuous series of bad-news feeds. There have been calls for greater security for Members of Parliament. Politicians, newspapers, television and social media have all been criticised for adding to a toxic public debate that many believe only encourages the violence. There are calls for more regulation of speech on social media platforms and stricter accountability. But what about MPs who call out ‘Tory scum’? Should there not be a reckoning for such language too? What is to be done?

We also had the first report from a House of Commons science committee on the government’s handling of the pandemic. Although it praises the vaccine rollout, it criticises the delay in enacting the first lockdown in March 2020. The Government’s modelers (SPI-M) allege that an earlier lockdown would have halved the death toll. In the meantime debates rage over vaccine mandates, vaccine passports, mask mandates, What is to be done?

Then we move onto climate change and from there the list goes on. The sense of lurching from one crisis to another always calls forth the same response: “What is to be done?” This happens to be the title of a pamphlet by Vladimir Lenin, the Marxist revolutionary who founded the Soviet Union. In it he stresses the importance of how we conceive of political problems and power.

“Lenin theorizes that workers will not spontaneously become Marxists merely by fighting battles over wages with their employers. Instead, Marxists need to form a political party to publicise Marxist ideas and persuade workers to become Marxists. He goes on to argue that to understand politics you must understand all of society, not just workers and their economic struggles with their employers. To become political and to become Marxists, workers need to learn about all of society, not just their own corner of it,” (Wikipedia article)

It may strike readers as odd to be quoting Marx and Lenin in an article about Buddhist principles, but there is a shared truth here, however far these two men may be from the Buddha’s spiritual message about suffering or dukkha. The Noble Eightfold Path starts with Right View, sometimes called Right Seeing. Here the Buddha makes the point that how we think about the problems we face (dukkha) - both individually and collectively - is even more important than what we think about them.

“It matters the thoughts you think with” is a phrase taken from the work of British anthropologist Marilyn Strathern, who studied the natives of Papua New Guinea. She believed that how we think about things conditions how we act, so we need to examine the concepts we use to navigate the world. As an anthropologist she observed people with completely different ways of seeing the world than her own. Therefore she cautions us against relying on normal habits of thought that result in inaccurate perceptions as well as inappropriate behavioural responses.

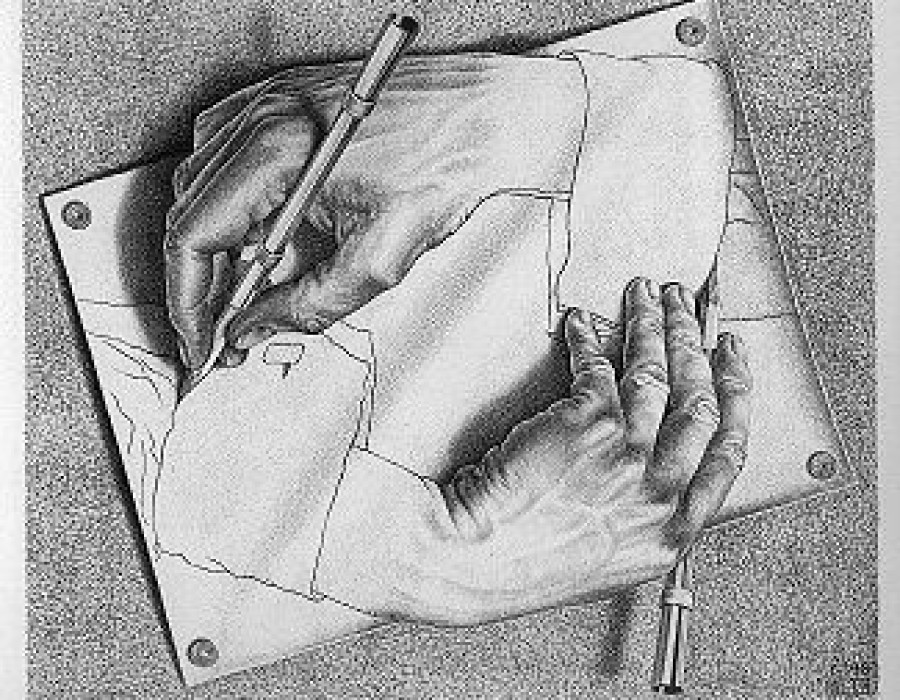

The Noble Eightfold Path is an extrapolation of the Buddha’s teaching of the Middle Way, the way between the opposites. It’s also the path that avoids clinging to a particular way of thinking. Master Hakuin refers to this in his great poem The Song of Meditation: “Take the thought of no-thought as thought.” This isn’t a call to turn the mind into a blank slate, which is not a natural function of the human mind. It asks us not to cling to our thoughts or our ways of thinking. As we face the many urgent problems in our world today, Hakuin’s advice is more pertinent than ever.

This article is itself a call for an on-going discourse, a conversation about how we should be viewing the many problems we currently face, so my first question is: ‘How do these issues look through a Buddhist lens?’ By this I don’t mean some kind of ideology based on Buddhist principles. The teachings of the Buddha transform the way we see things. It’s no coincidence that Right Seeing is followed by Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action and Right Living. As Marilyn Strathern points out, how we think flows into how we act in the world. If we can see more clearly then we’re likely to act less ignorantly in our dealings with the world. It’s like the man who every night dreams of being chased by a hungry tiger. The dream terrifies him so he places a loaded shotgun underneath his bed. Failure to realise that a material gun is useless for dispatching a dream tiger means that our real problems will persist.

To navigate the world we need to understand the nature of the world. In the next part we’ll explore contrasting ways of thinking. We’ll look at how thinking differently changes the way the world appears to us and how we perceive our problems.

The Zen Gateway Blog

Dharma, Culture, Philosophy & Life-ways