Psychopaths, altruists and the persuasive power of the podcast

Blog

Rachel Hilton takes a look at what Psychopaths can teach us about compassion.

©

©

One of my guilty pleasures is listening to podcasts on my daily commute and I was recently listening to a podcast hosted by a Yale professor of psychology on the subject of empathy.

I will digress for a moment to discuss the difference between sympathy, empathy and compassion. Sympathy is when we understand the feelings of another person without necessarily sharing those feelings, so, for example, when someone is bereaved we understand their grief, we sympathise, speak kind words and may perhaps send a sympathy card. Empathy takes this up a notch in that we not only understand what a person is feeling but we also quite literally share that person's emotions; so, for example if I slam my fingers in the door you might wince at the pain; if I am bereaved and start to cry, you might cry with me, even if you don't know the person who has died. Compassion drives sympathy or empathy up a notch further still because we not only understand or even share another's emotions but we are then motivated to take action to alleviate their suffering, and this of course is particularly emphasised in the Bodhisattva Ideal.

But back to the podcast: the research that was being discussed was undertaken by a Washington psychologist who was inspired by a random act of kindness from a stranger to study the nature of altruism; she began by studying individuals who are highly deficient in empathy and compassion, namely psychopaths. Now, a quintessential psychopath is someone who is consistently callous in the face of another’s suffering. And, as an aside, although in the popular imagination psychopaths are people who indulge in antisocial behaviour such as sex offenders and serial killers, there are many people with psychopathic traits who are very successful in the workplace, particularly in senior management, in the media and in sales. You may have met one and you may even work with one! However, while superficially charming, psychopaths lack both fear and empathy and it transpires that there is a specific area in the middle of the brain called the amygdala which is primarily involved in processing the emotions and memories associated with fear. The amygdalae of psychopaths are smaller than normal, and less responsive when the subject is shown images of frightened faces. So, this may explain why psychopaths behave as they do. Their underdeveloped amygdalae impair both their ability to feel fear themselves, and their ability to recognise other peoples’ fear. Hence, they are biologically incapable of empathising with others.

Happily, there are other people who have empathy in abundance, and the other group of people that this same researcher studied, the anti-psychopaths if you will, were altruistic living kidney donors. This is where my ears pricked up because this is a group of people I have been working with for many years and in whom I have a keen interest.

Altruistic living kidney donors are people who choose to donate one of their kidneys to a complete stranger who has kidney failure, whom they will never meet nor hear from, and they do this simply because “they can”. These “extreme altruists” are truly remarkable people, perhaps the most remarkable thing being that they don’t consider themselves to be remarkable at all. For them, to risk death and to endure pain and hospitalisation for no reason at all other than that someone somewhere will benefit from a kidney transplant and escape from dialysis, is as obvious and natural as breathing. When I delve into their backgrounds, they have almost all spent a lifetime doing good, as doctors, teachers, priests, and carers, they have donated blood and they have given time and money to charity. They do this in total anonymity and are genuinely astonished that we do not all do the same! They are truly modern- day Bodhisattvas.

And here is the kicker: when tested in the laboratory, altruistic kidney donors recognised fearful expressions more readily and more accurately than normal controls, their amygdalae were more active when doing so and the amygdalae were larger in volume than the amygdalae of non-altruistic controls.

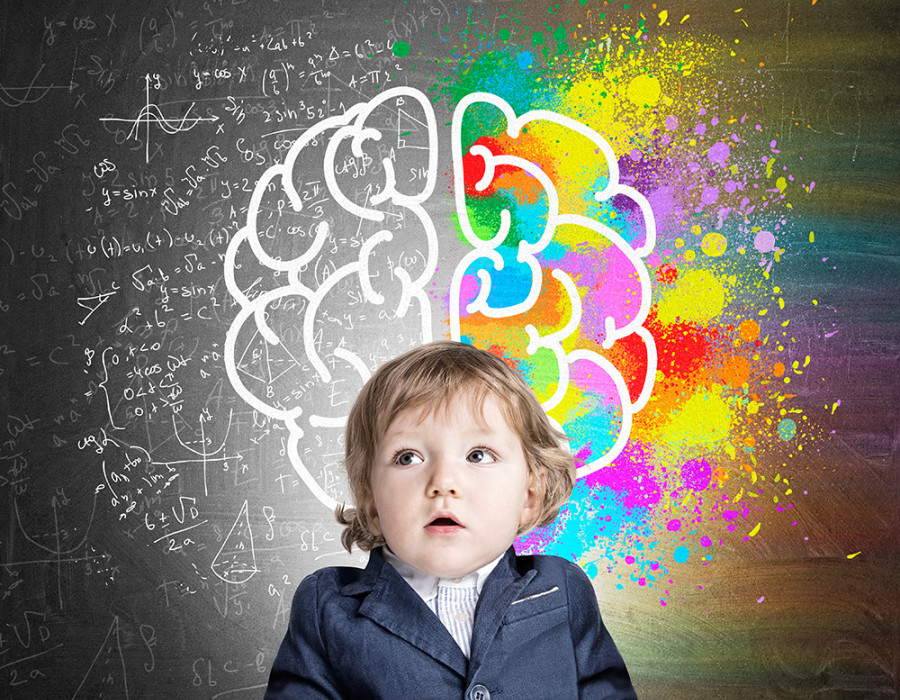

So here is the question: is the ability to empathise down to nature or nurture? If your amygdala is well developed and active does that turn you into a compassionate person? Or if you practice compassion, will that in time change the shape of your brain? The reality is probably a little bit of both – and while some people may come by altruistic behaviours more readily than others, we can all do things that help foster better behaviours in ourselves and others. Practicing empathy and compassion is surely a skill worth developing, and, if we believe the science, doing so may change the shape and activity of our brains in a way that makes us even more likely to behave in an empathic and compassionate way.

So, if we can be kinder to ourselves and each other, by doing so we will become kinder people. And I will start by feeling less guilty about my podcast hour...

The Zen Gateway Blog

Dharma, Culture, Philosophy & Life-ways