Flag Waving: Reflections on two monks discussing a fluttering flag.

A Dharma Essay

Clear seeing arises in the absence of partiality, however this is not something that 'I' can do as 'self' is dependent upon partial seeing in the first place. This impacts on any notion that 'I' can solve the problems that 'I' make.

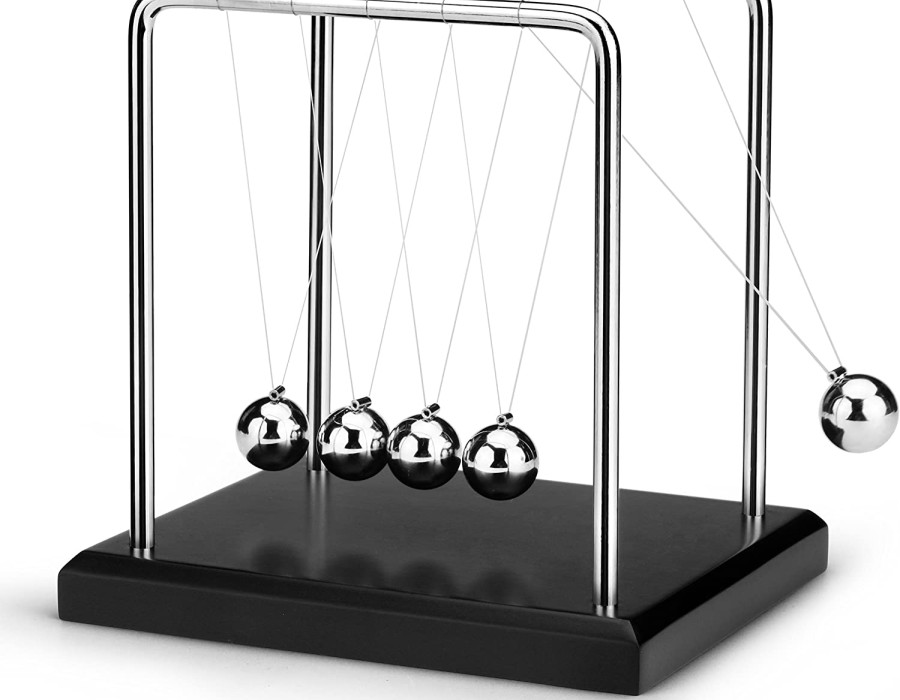

Newton's Cradle

“Two monks seeing a flag fluttering in the wind, started discussing it. One said: ‘It is the flag that moves.’ The other held: ‘No, it is the wind that moves the flag.’ The argument went to and fro. Master Eno stepped up to them: ‘It is neither the flag nor the wind, but the hearts of the two brothers that are flapping.’”

The Wisdom of the Zen Masters by Irmgard Schloegl

…

This story of the Sixth Patriarch Eno Daikan (638-713) of the Chinese Zen school is a staple of many a collection of stories from the Zen canon.

It is often used to highlight a very human tendency to take sides in an argument and become entrenched, identifying myself with the ‘cause’ and then defending it as if my life itself has been put on the line. The master in these stories represents the Buddha-seeing of the situation which disentangles the narrowed perspective of ‘I’ from the fact that both sides are engaging in what the ecological activist, thinker and writer, Charles Eisenstein, calls an act of ‘separation’. What we see in the story above are two views, one from each side, and then the master’s, who keeps the two conjoined by pointing out what they share in common. Holding these two sides together, is imperative if we, as individuals, are not to become atomised by the delusion of ‘self’.

In the 2nd Noble Truth, the Buddha cites the origin of our suffering as craving, but more specifically, it is attachment to this tendency to separate myself out and deny the links of dependency and commonality that tie us into the world of light and dark. But the Buddha also taught the Middle Way, so perhaps even this tendency to separate, can play an important role in life too.

As a middle-aged man who married another man a little over two years ago, witnessed by friends, family and conducted by the local municipal registrar, it can be easy for me to forget how different attitudes were a few decades ago growing up in the 1970s. I was a church-going Catholic teenager wrestling with a growing awareness that my sexuality was at odds with many of my contemporaries. I was acutely aware that I was ‘one of those’, and that this could make me a target for social opprobrium from those same friends, family and figures of authority, both religious and secular. In the end, when I finally did ‘come out’ to friends and family it turned out to be a positive and accepting situation quite different from ‘my’ expectation. What strikes me now is how there were many instances where in my own heart I, too, was ‘demonising’ others whom I had made ‘the enemy’ of ‘my’ sexuality. Of course, I did sit through church sermons where homosexuality was denounced, my friends did mock people whom they identified as ‘queer’, as, to my shame, did I. What I felt at that time, in connection with my thinking on all this was a mixture of rage and fear.

Both these emotions have the role to separate out, in order to protect. The aggressive instinct is often used this way in nature, to protect territory or the young. In my own case it was to create and protect mental territory so that I could work out my own thoughts and feelings about what was emerging. The threat was of being overwhelmed by the thoughts and feelings of others, particularly anyone seen as authoritative.

What is noticeable is that ever since that time, I’ve never entirely trusted the views of the consensus. When in a group where everyone is agreeing on what is ‘right’ or what is ‘true’, my own mind is looking to what is being excluded - the marginalised view. What is noticeable is how quickly the consensus moves into a more sanctioning mode that seeks to preserve consensus and mocks or looks down on what it itself has marginalised.

A few years ago, a Zen practitioner once confessed to me that he had had a rude awakening about himself that conflicted with an important self-belief. He said: “You know, I always thought of myself as being open-minded, but I’ve recently realised that in fact I can be quite a bigot!” What he meant was that this ‘bigotry’ was not against the usual targets that we might associate with the word but against other things that to ‘me’ might seem self-evident; however, his blindness, derision of difference and dismissal were just as narrow as many of the views I had come across in my own teen years. Of course, he was just being honest and we both knew that he was not alone in doing this!

In taking sides, there is a shared dynamic at work. Just as the Sixth Patriarch points out that the two monks, on opposite sides of a divide are in fact participating in the same process, so it is with us either individually or when engaged in collective debate. The teaching on ‘dependent origination’ came through to China and began to be expressed in accordance with Chinese thought - that is - the inter-dependency of the opposites. This is best expressed in that Chinese symbol the YinYang. A circle, or whole, is made up of two fish-like shapes one white and one black. Walking along the tail of the white fish it grows in thickness until we reach the ‘head’ where a black eye is placed. The white fish ends and we find ourselves upon the tail of the black fish, and so it goes on. What this symbol demonstrates is that each thing contains the ‘seed’ of its opposite. In my own case, the consensus triggers in me a search for the marginal. The expression of the marginal creates a defensive reaction in the consensus, and so on. This would seem to be an important psychological law that we should know and be aware of in our own interactions.

The other insight the YinYang shows is that it is a closed system; we are forever swinging on a pendulum, moving through time, so it describes a continual wave motion that never exactly covers the same ground but is destined to move within a carefully prescribed range that will repeat and repeat. Is this not the very definition of samsara as described on The Wheel of Life? One time it may be ‘Remain or Leave’, then ‘pro-lockdown or anti-lockdown’ and then ‘Biden or Trump’. It seems we are always trapped in this narrative carefully prescribed and self-perpetuating. What is the master’s view here?

What is the solution here?

Returning to Charles Eisenstein, in his book Climate: A New Story, he cautions that our very mode of thinking about these things may be part of the problem and he warns against what is termed ‘solutionism - the belief that all problems can be solved by the use of technology. The very act of ‘my’ trying to create a solution, because ‘I’ am trapped in the process of dependent origination that creates these problems, can only exacerbate and perpetuate and seed future problems. As Yoka Daishi said: “It is like throwing oneself into fire to avoid being drowned.”

The Buddha says in the Pali Canon that to see dependent origination clearly is to see the Dharma. It is not clinging to the ‘right view’ that is the solution but recognising how ‘I’ perpetuate the problem through my clinging.

Is there not the exasperated thought arising: “Well, what am I supposed to do then?

Indeed!

…