Martin Goodson

The Holy Scripture of Vimalakirti

The Vimalakīrti Sūtra

Our retelling of the Vimalakirti Nirdesa returns. In this episode, the Buddha shows an assembled crowd a vision of cosmic proportions.

©

© Shutterstcok

The Vimalakirti Nirdesa (The Holy Scripture of Vimalakirti) is a sutra from the Mahayana cycle known as the Prajnaparamita or Wisdom Gone Beyond sutras. The Heart of Great Wisdom sutra, that most popular of chants, also belongs to this cycle.

There are a number of core Buddhist teachings to be found in the Vimalakirti sutra. These include discourses on Emptiness, the bodhisattva path to buddhahood and why this path is open to all.

In most sutras, the main protagonist is the Buddha himself, the great teacher who after awakening under the bodhi tree spent the remaining forty-five years of his life making available the Way for those inclined towards it. This sutra is unique in that the main protagonist is the somewhat mysterious figure of Vimalakirti. He is undoubtedly a great bodhisattva. He can make arhats uneasy and cause even those who have attained the rank of bodhisattva to feel queasy about engaging him in conversation on anything to do with the Dharma.

Vimalakirti is not even a monk. He’s a layman. In fact, he is a wealthy merchant from the ancient capital city of Vaisali, located in northeast India in the modern province of Bihar. This makes him stand out from the other characters who appear in this sutra or indeed in most other Buddhist scriptures.

The consensus view of the time was that spiritual attainment was only possible for those who left home and lived in remote forests and mountains - something that was not an option for men and women householders - so Vimalakirti was a radical protagonist. Yet the very point of Mahayana Buddhism is that a bodhisattva must live in and engage with the world. The training ground is wherever one happens to be. There is no special place to go. It is found right under one’s own feet.

The Vimalakirti sutra has always been popular with the Zen school. Famously, Chan/Zen is not dependent on words and scriptures. This isn’t to say that it does not use them, only that words are seen as pointers along the way, and cannot act as a substitute for one’s own insight.

One more quality that makes this sutra stand out from many of its peers is its use of humour.

The Mahayana schools tended to use earlier conceptions of attainment as the butt of their jokes. The arhats, with their austerities and somewhat superior attitude, ended up being brought down a peg or two. All this is in the Vimalakirti sutra as well, but here even the bodhisattvas don’t get away with any complacency. In the face of this formidable layman, Vimalakirti, they are also shown to be lacking in some cases and tremulous in the face of having their understanding challenged. This is the equivalent of portraying the apostles in the New Testament as being well-meaning but essentially dim!

Over the next few months, we plan to retell some of the stories from the Vimalakirti sutra in our modern idiom. Hopefully, the reader will not only find them entertaining but will also appreciate some of the more profound teaching points they were meant to convey.

The Miracle of the 500 Parasols

The Buddha travelled extensively in eastern India during his long life accompanied by a vast retinue of monks. He was always made welcome but the size of his entourage often required temporary accommodation on some tract of land donated by a king or wealthy follower.

Local people would come bearing gifts of food and other necessities of life. They would queue up to present these to the retinue of monks. No doubt some of the donors hoped that their rice or lentil stew or cloth to make new robes for the monks would be presented to someone really important. Maybe it would be one of the great arhats like Sariputra or Maudgalyayana. Maybe it would be the Buddha’s own cousin and personal assistant, Ananda, or perhaps even one of the great bodhisattva-mahasattvas such as Manjushri, a crowned blue-skinned prince with a flaming sword of wisdom. Best not stand too close! And, of course, there was always the possibility of it being the Buddha himself.

On one such day, the local populace assemble in a park on the edge of a town called Amrapali near the great city of Vaisali. By all accounts it is a very nice place to relax, with cultivated gardens, orchards, fountains, flowers and beautiful animals to provide respite from the hot sun.

This is fortunate because the crowds are enormous. Men, women and children have all come to see the spectacle. There are several arhats, sitting serenely in meditation, undisturbed by the hubbub of the milling throng. One of them sits so still, his breathing so quiet, that a little boy prods him to see if he is still alive.

Overhead an aerial formation of bodhisattvas, beautifully attired in heavenly clothes and spectacular jewellery, fly here and there to assist the swelling crowd. One moment they rescue an old lady in danger of being trampled underfoot; another moment they reunite a little girl with her anxious parents. Tempers fray as thousands of people get stuck trying to get through to the park.

The bodhisattvas swoop down and collect the gifts and in return provide wonderful ambrosia to the hot and hungry crowd. This ambrosia is, of course, the Dharma, but it satisfies even the hungriest appetite. They also offer words of comfort to the waiting crowds, their voices so harmonious that the anger and frustrations of the people are forgotten as they calmly listen to this most beautiful of sounds.

At the far side of the throng sits the majestic Buddha himself. His body shines like gold, radiating the light of compassion and wisdom. He sits upon a mighty throne shaped like a lion, the symbol that denotes the Lion’s Roar of the Dharma. He waits patiently to begin his teaching.

At this point the lay teacher Ratnakara leads a retinue of minor bodhisattvas toward the Buddha. They are 500 in all and each one has an exquisite parasol to protect himself from the sun. This is their offering to the Buddha and the sangha. As each bodhisattva reaches the Buddha he turns and circumambulates clockwise around the Lion Throne to show his respect, before laying down his offering.

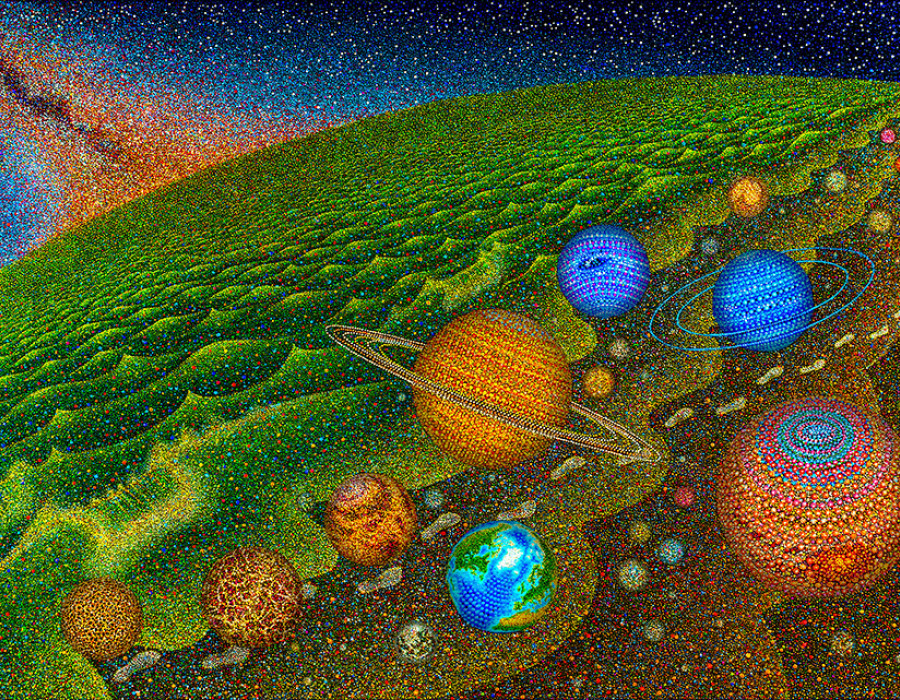

As soon as the last parasol touches the ground the Buddha stretches out his hand. Immediately the 500 separate parasols become one almighty parasol. The Buddha lifts this parasol and as he does so it opens up. It is so vast that it stretches out and covers everything. The crowd gasps in awe. They look up and see the most wondrous sight on the inside of the great parasol. Even the arhats open their eyes and stare up at it. The bodhisattvas in flight are doing a backstroke through the air so they too can see the mighty vision unfolding within the parabola on the inside of the parasol.

There, reflected in the parasol above the crowd, is the whole earth with its mountains and valleys and oceans; with its towns, cities and countries; with its mighty rivers, gurgling brooks and wide open spaces. On further inspection it is not just this world that is reflected there, but all the worlds: the six realms, the gods in the heavens and the miserable beings in the 16 hells. There are other Buddhas teaching in galaxies that no-one has even heard of before. The vision goes on and on because there is no end to what can be reflected on the inside of this wonderful parasol.

Everyone, including the arhats, the devas who are also there - if invisible to most of the people - and the flying bodhisattvas who have landed, press their palms together and bow in admiration of the wonderful vision of the Buddha.

Finally, the Buddha presses his palms together too and withdraws to one side.

The Vimalakīrti Sūtra | Martin Goodson

Stories Retold