The Wheel of Truth by Ajahn Sumedho

Book Extracts

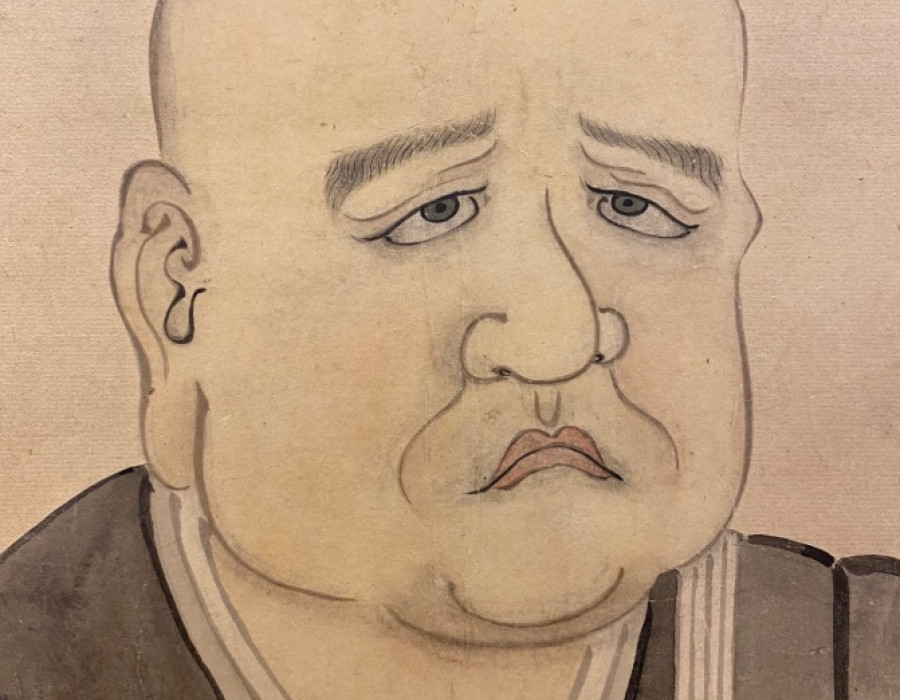

Ven. Ajahn Sumedho recounts his experience as an 'arrogant', 'stubborn' and 'rebellious' foreigner, starting life as a monastic in very harsh conditions in the north of Thailand.

©

©

Before I became a monk, I was teaching English in Bangkok. It was 1966, and there were a lot of American Air Force bases in Thailand. One of the teachers at the language school was an American airman. Once, when he came back after an absence of a week or so, I asked him where he’d been. He said, ‘I’ve been to a place in North East Thailand where the people are so poor they have to eat insects.’ I thought, ‘I’m never going there.’ I imagined myself instead as a monk sitting in samādhi on the beach under a palm tree or in a cave among beautiful mountains, realizing the truth. Of course, I ended up as a monk in the North East of Thailand for ten years, and it’s true – they eat insects.

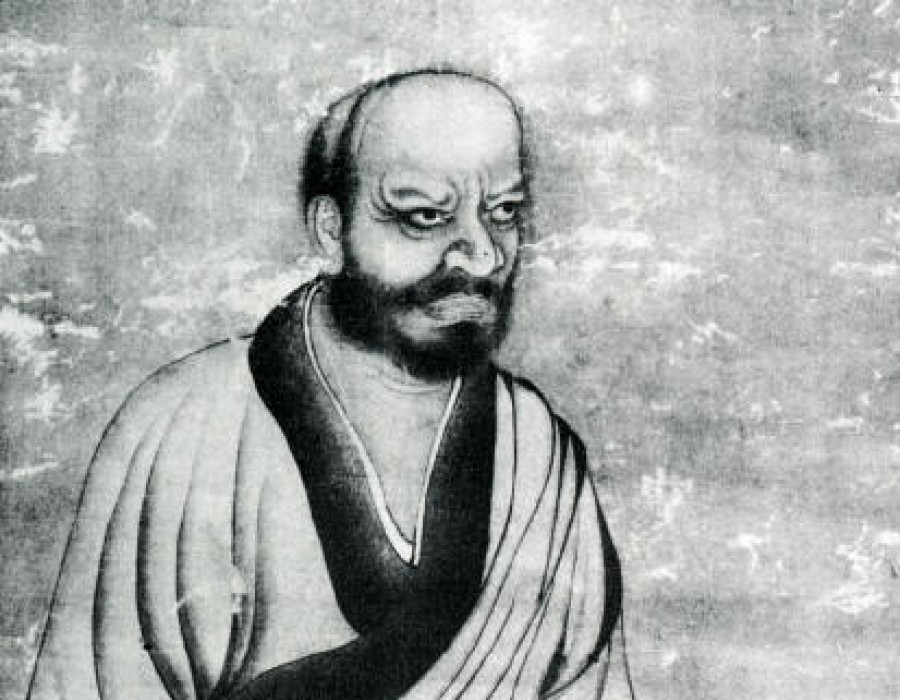

The first year I spent alone in a monastery, living in a little hut. I didn’t really associate with anybody – just practised meditation. I set my own agenda. As a big, tall American, I could just puff out my chest, look fierce and get almost anything I wanted. During that year, I came to see that I had a lot of arrogance and the sort of character that needed limits. I had always been a very independent person, so I needed to learn how to serve in a community. I needed a teacher who wouldn’t put up with my behaviour. Then, by chance, I met a monk from Ajahn Chah’s monastery – the only one who could speak English – and he ended up taking me back to meet Ajahn Chah. So I went to Wat Nong Pah Pong in Ubon, Thailand, in 1967 with the idea of training myself in a strict tradition.

The following ten years spent with Ven. Ajahn Chah gave me every possible opportunity to adapt to change and to learn to let go of my personal preferences. The frustration, resistance and annoyance that I experienced were eventually transformed into a deep and profound sense of gratitude and love. The harsh edges of ego and conceit began to wear away as the years passed by. The Thai Forest Tradition was an ideal I found very inspiring, so at first I was entranced and uplifted, but the realities soon appeared. The weather got hot, the monsoon season started, and everything turned rotten and stinky. I began to hate the place. I remember sitting there thinking, ‘Why am I here?’

In those days, Ajahn Chah loved testing our patient endurance to the point where we didn’t think we would be able to last another moment. I’d hear myself saying, ‘I can’t take any more of this ... I’ve had enough. This is the END!’ Then I’d find out I could endure more. I began to distrust this inner hysterical screaming in me. The monastic form and the conditions helped a lot, but being brought up with an egalitarian ideal of freedom and equality, I felt an incredible frustration in being suffocated by the system. I was living in a hierarchical structure based on seniority, and because I was the most junior monk there, I had to perform certain duties for those who were senior to me. Learning to acknowledge and to take an interest in performing them was quite a challenge. There was a selfish side in me that wanted to live monastic life on my own terms. I was willing to perform duties if it was convenient for me, but much of the time it wasn’t. I felt resistance and rebelliousness. At the same time, the teachings continually encouraged me to acknowledge what I was feeling – the resistance, the rebelliousness, the criticism. I became aware of my stubbornness and an immaturity that grumbled and complained if things didn’t suit me. The emphasis was on cultivating mindfulness of what I was feeling: I wasn’t simply browbeaten into conformity like it was a military camp. Nobody pushed me into that place; I chose to live there. My agreement was to conform to the discipline, to surrender and learn to adapt to this very strict and conservative monastic lifestyle. This included learning to eat food that I didn’t particularly like. Villagers would bring nice little curries with chicken, curries with fish, curries with frog, but in those days, Ajahn Chah would dump them all into a big basin and mix it up. It made me sick to even look at it. Fortunately, it was mango season, and there were big trays of mangoes. I managed to live on mangoes and sticky rice for an entire month, but after the mango season ended I started getting thinner and thinner. Finally, I learned how to eat the food – it is surprising how well we can adapt.

Copywrite Amaravti Publications