Martin Goodson

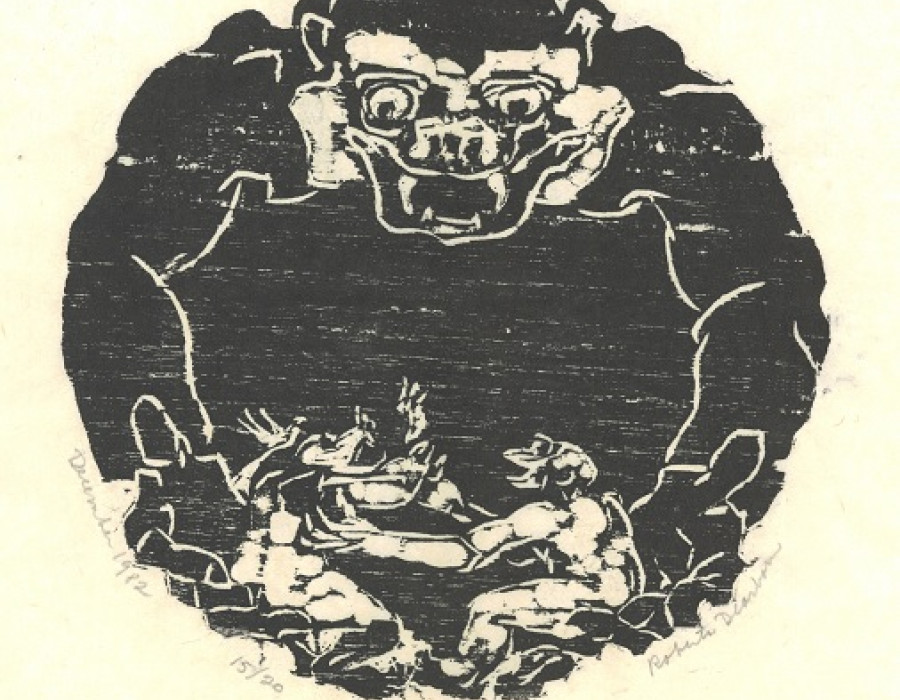

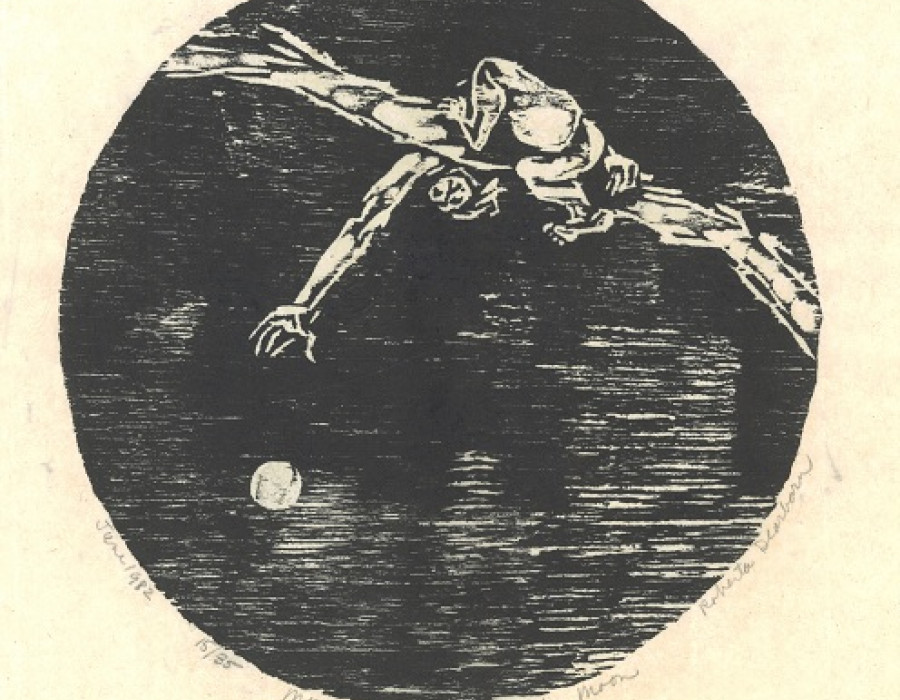

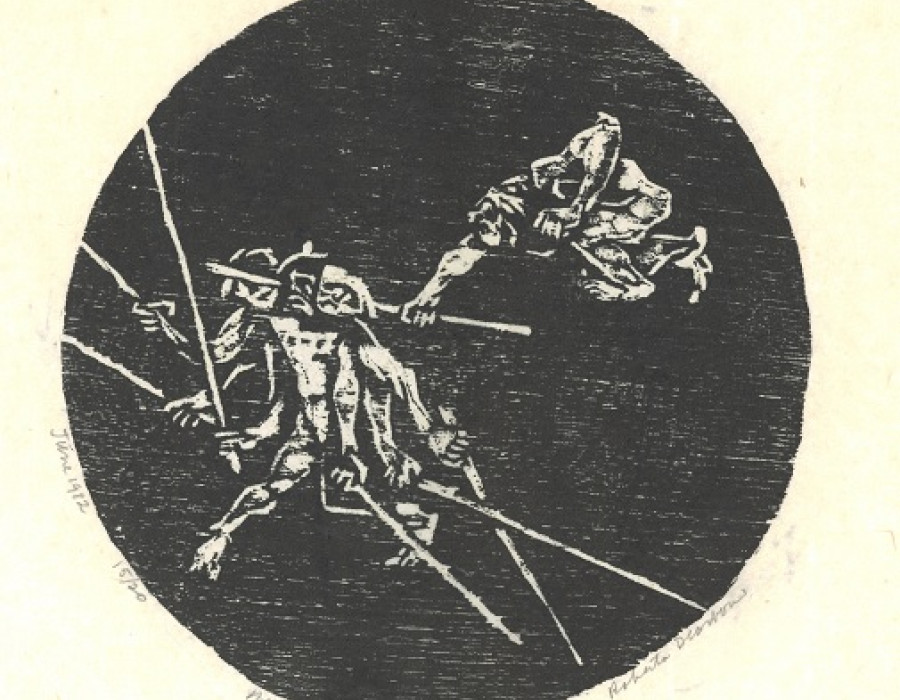

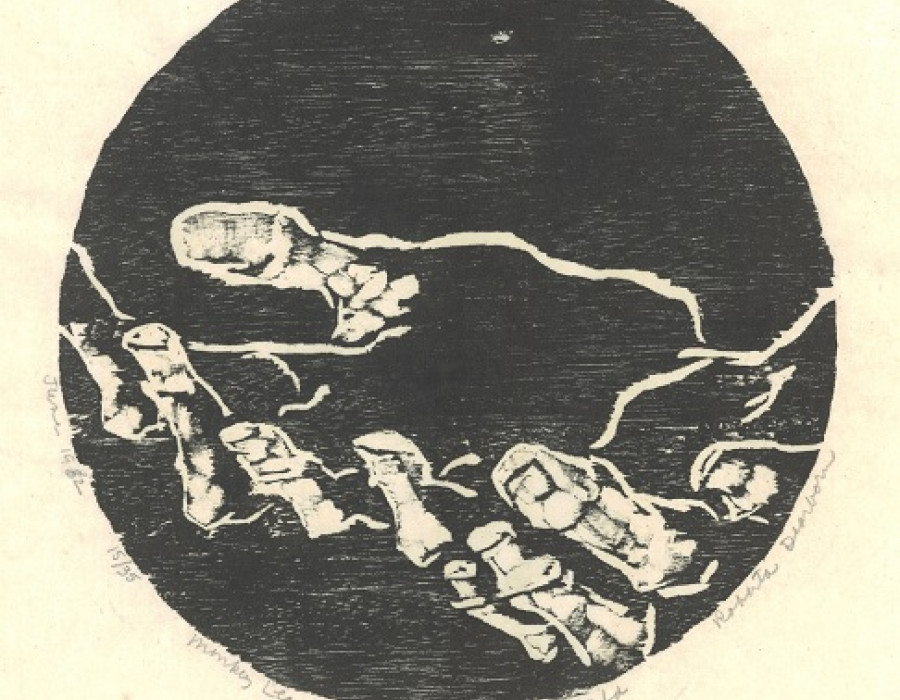

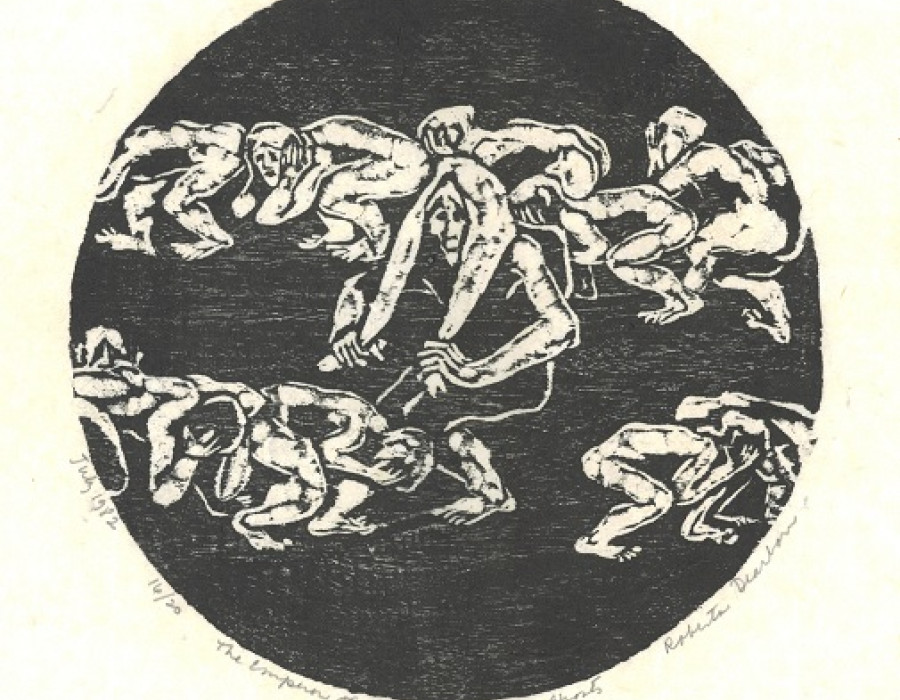

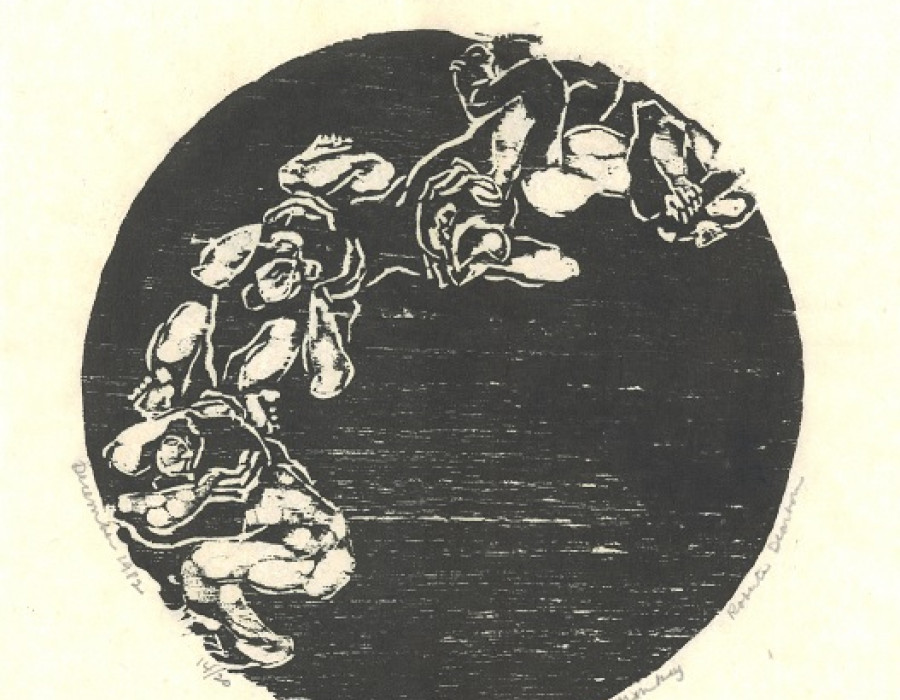

Introduction to the Stories of Monkey | With illustrations by Roberta Mansell

Stories Retold

Born from a rock, possessing magical powers to rival the Gods and imprisoned under a mountain by the Buddha, the Character of Monkey has been the subject of TV shows, films and Operas.

Monkey: Brave New World by Roberta Mansell

Roberta Mansell

‘Monkey’, originally written by a minor Ming dynasty poet in the 16th century, is an epic tour de force and a comic satire full of warmth and humour. Also known as ‘Journey to the West’, it is one of only a few examples of Chinese classic literature that have been translated into English. Perhaps the most notable translation of ‘Monkey’ was by Arthur Waley, in the middle of the last century.

As Waley tells us in his introduction:

“Tripitaka, whose pilgrimage to India is the subject of the story, is a real person, better known to history as Hsuan Tsang (Xuanzang). He lived in the 7th century A.D., and there are full contemporary accounts of his journey. Already by the 10th century, and probably earlier, Tripitaka’s pilgrimage had become the subject of a whole cycle of fantastic legends.”

‘Monkey’ is extremely long and is therefore usually produced in abridged form. Waley’s translation is a selection of the stories from the original work in which Monkey and his companions accompany the monk Tripitaka to India in order to collect Buddhist scriptures and bring them back for the Chinese Emperor. Each character represents a facet of humanity in disguised form. As Waley explains:

“Tripitaka stands for the ordinary man, blundering anxiously through the difficulties of life, while Monkey stands for the restless instability of genius. Pigsy, again, obviously symbolizes the physical appetites, brute strength and a kind of cumbrous patience. Sandy is more mysterious. The commentators say that he presents ‘ch’eng', which is usually translated ‘sincerity’, but means something more like ‘whole-heartedness.’ "

Heaven and the gods play a major role in Monkey and are the butt of many jokes. We should understand that Heaven, the Jade Emperor and all the gods and ‘fairy’ officials are simply the Chinese Imperial Court transferred to the empyrean. We also meet Taoist Immortals, Sages and Patriarchs, and of course the Buddha as well as several bodhisattvas. However, Wu Ch’eng-en spares neither holy men nor so-called saints and his barbs have a familiar ring. Rivalries and petty jealousies that have peppered the history of religion down the centuries are as prevalent in our own times as they were then. If the reader has a good understanding of Buddhism and Taoism, the text’s deeper meaning becomes apparent. It is fair to say that some of the incidents recounted in Monkey point to a profound understanding of spiritual matters asthrough Chinese thought.

Roberta Mansell, friend of The Zen Gateway, whose images from the Lotus Sutra we exhibited for many years, has supplied images to illustrate our excerpts. Originally these images were to illustrate a reprint of the Waley edition and, although that project did not materialize, we express our sincere gratitude to Roberta for allowing us to exhibit these images.