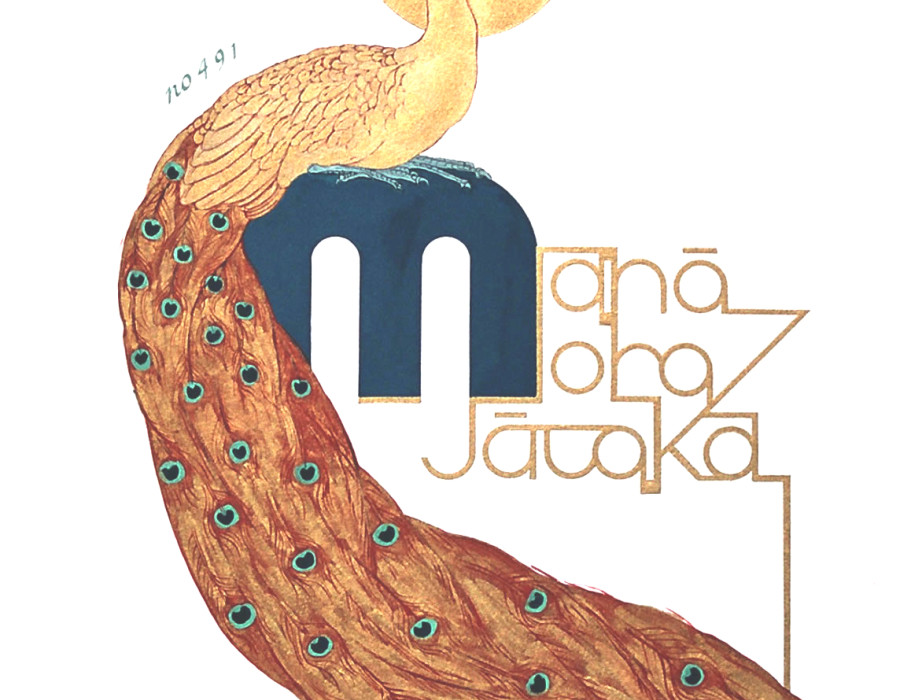

An Illustrated Jātaka:Mahāmora-jātaka (part 2)

The Tale of the Golden Peacock illustrated by Roberta Mansell

The Golden Peacock Swinging

Roberta Mansell

But the seventh hunter, sent by the seventh king, being unable to catch the bird through seven years, although each day he expected to do it, began to wonder why there was no catching this peacock's feet in a snare. So he watched the bird, and saw him at his prayers for protection morning and evening, and thus he argued the case: "There is no other peacock in the place, and it is clear this must be a bird of holy life. It is the power of his holiness, and of the protecting charm, which makes his feet never to catch in my snare."

Having come to this conclusion, he went to the borderland and caught a peahen, which he trained at finger-snap to utter her note, at clap of hand to dance. Taking her with him, he returned; then setting his snare before the Bodhisattva had recited his charm, he snapped his fingers, and made her utter a cry. The peacock heard it: on the instant, a karmic seed which for seven thousand years had lain quiescent, reared itself up like a cobra spreading his hood at a blow. Being sick with lust, he could not recite his protecting charm, but making all haste towards her, he came down from the air with his feet right in the snare: that snare which for seven thousand years had no power to catch him, now caught his foot fast. When the hunter spied him dangling at the end of the stick, he thought to himself, "Six hunters failed to catch this king of the peacocks, and for seven years I could not. But to-day, as soon as he became lust-sick for this peahen, he was unable to repeat his charm, came to the snare and was caught, and there he dangles head downwards. So virtuous is the being which I have hurt! To hand over such a creature to another for the sake of a bribe is an unseemly thing. What are the king's honours to me?

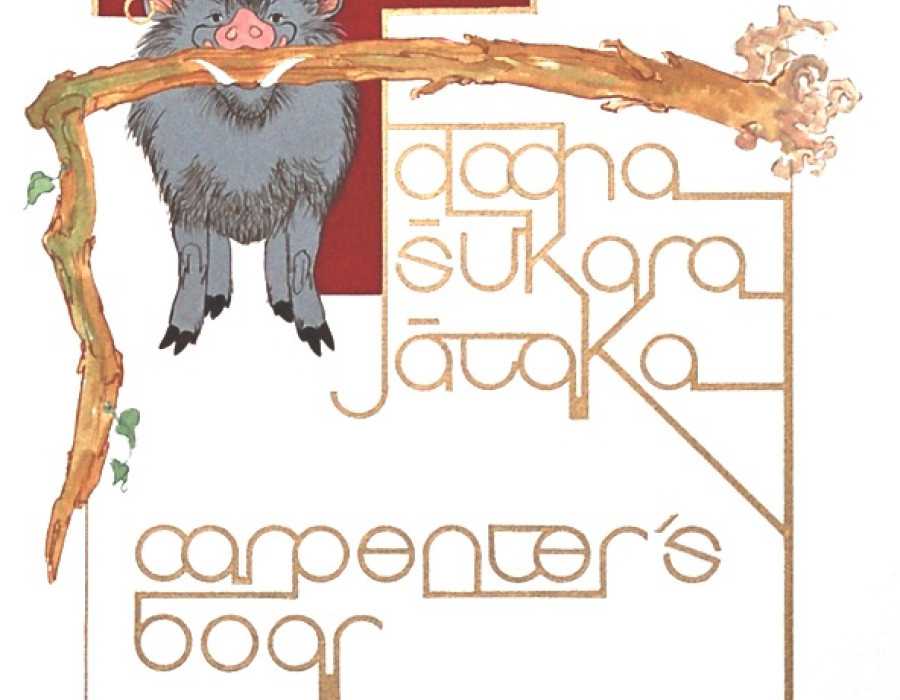

Peacock & Hunter

Roberta Mansell

I will let him go." But again he thought," “Tis a monstrous mighty and strong bird, and if I go up to him he may think I have come to kill him, he will be in fear of his life, and in struggling he may break a leg or a wing. I will not go near him, but I will stand in hiding and cut the snare with an arrow. Then he can go his ways at his own will." So he stood hidden, and stringing his bow fitted an arrow to the string and drew it back.

Now the peacock was thinking, "This hunter has made me sick with lust, and when he sees me caught he will not be careless of me. Where can he be?" He looked this way, and he looked that way, and spied the man standing with bow ready to shoot. "No doubt he wants to kill me and go," thought he, and in fear of death repeated the first stanza asking for his life:

"If I being captured wealth to thee shall bring,

Then wound me not, but take me still alive.

I pray thee, friend, conduct me to the king:

Methinks a most rich guerdon he will give.”

Hereupon the hunter thought, "The great peacock imagines I am going to shoot him with this arrow: I must relieve his mind," to which end he recited the second stanza:

"I have not set this arrow to the bow,

To do thee hurt, O peacock king, to-day:

I wish to cut the snare and let thee go,

Then follow thy own will, and fly away."

To this the peacock replied in two stanzas :

"Seven years, O hunter, first thou didst pursue,

Enduring thirst and hunger night and day:

Now l am in the snare, what wouldst thou do?

Why wish to loose me, let me fly away?

"Surely all living things are safe from thee:

Taking of life thou hast forsworn this day:

For I am in the snare, yet thou wouldst free,

Yet thou wouldst loose me, let me fly away."

Insightful Hunter

Roberta Mansell

Then this follows:

"When a man swears to hurt no living thing:

When all that live, for him, from fear are free:

What blessing in the next birth will this bring?

O royal peacock, answer this for me?"

"When all that live, for him, from fear are free,

When the man swears to hurt no living thing,

Even in the present world, well praised is he,

Him after death to heaven his worth will bring."

"There are no gods, so many men do say:

The highest bliss this life alone can bring;

This yields the fruit of good or evil way;

And giving is declared a foolish thing.

So I snare birds, for holy men have said it:

Do not their words, I ask, deserve my credit?"

Then the Great Being determined to tell the man the reality of another world; and as he swung at the end of the rod head-downwards, he repeated a stanza:

"All clear to vision sun and moon both go

High in the sky along their shining way.

What do men call them in the world below?

Are they of this world or another, say?"

The hunter repeated a stanza:

“All clear to vision sun and moon both go

High in the sky along their shining way.

They are no part of this our world below,

But of another: that is what men say."

Then the Great Being said to him:

"Then they are wrong, they lie who such things say;

Without all cause, who say this world can bring

Alone the fruit of good or evil way,

Or who declare giving a foolish thing."

As the Great Being spoke, the hunter pondered, and then repeated a couple of stanzas:

"Verily this is true which thou dost say:

How can one say that gifts no fruit can bring?

That here one reaps the fruit of evil way

Or good; that giving is a foolish thing?

"How shall I act; what do, what holy way

Am I to follow, peacock king, O tell!

What manner of ascetic virtue – say,

That I be saved from sinking into hell !"

The Great Being thought when he heard this, "If I solve this problem for him, the world will seem all empty and vain. I will tell him for this time the nature of upright and holy ascetic brahmins." With this intent he repeated two stanzas:

"They on the earth, who hold the ascetic vows,

In yellow clad, not dwelling in a house,

Who go forth early for to get their food,

Not in the afternoon: these men are good.

"Visit in season such good men as these,

And question anyone it shall thee please:

They will explain the matter, for they know,

About the other world and this below."

Thus speaking, he terrified the man with the fear of hell. The other attained to the perfect state of a Pacceka [skt. Prayeka - a Buddha who seeks liberation for himself] Buddha; for he lived with his knowledge on the point of ripening: like a ripe lotus bud looking for the touch of the sun's rays. As the hunter hearkened to his discourse, standing where he was, he understood all in a moment the constituent parts of existing things, grasped their three properties [Three Signs of Being], and penetrated to the knowledge of a Pacceka Buddha. This comprehension of his, and the setting free of the Great Being from the snare, came both in one instant. The Pacceka Buddha, having annihilated his lusts and desires, standing on the uttermost verge of existence, uttered his aspiration in this stanza:

"Like as the serpent casts his withered skin,

A tree her sere leaves when the green begin:

So I renounce my hunter's craft this day,

My hunter's craft for ever cast away."

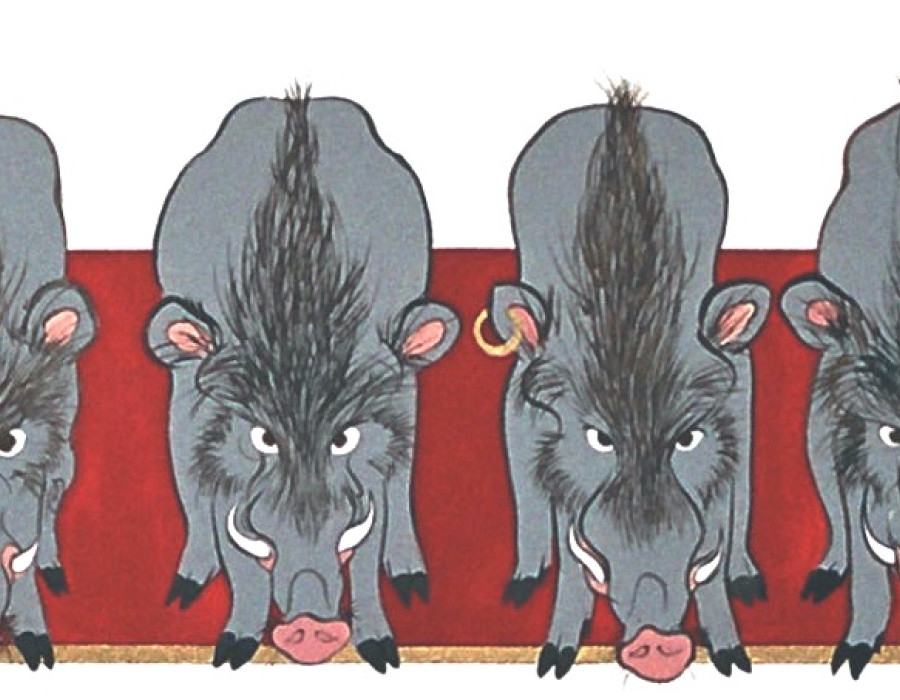

Having uttered this sublime aspiration, he thought, "I have just now been set free from the bonds of sin; but at home I have many a bird held fast in bondage, and how am I to set them free.

Birds Released

Roberta Mansell

So he asked the Great Being: "King Peacock, there are many birds I left in bondage at home, how can I set them free?" Now the Bodhisattvas, who are omniscient, have a better knowledge and comprehension of ways and means than a Pacceka Buddha; therefore he answered, "As you have broken the power of lust, and penetrated the knowledge of a Pacceka Buddha, on that ground make an act of Truth, and in all India there shall be no creature left in bonds.” Then the other, entering by the door which the Bodhisattva thus opened for him, repeated this stanza, making an Act of Truth:

"All those my feathered fowl that I did bind,

Hundreds and hundreds, in my house confined,

Unto them all I give their life to-day,

And freedom: let them homewards fly away."

Then by his Act of Truth, though late, they were all set free from confinement, and twittering joyously went home to their own places. At the same moment throughout all India all creatures bound were set free, and not one was left in bondage, not so much as a cat.

The Pacceka Buddha uplifted his hand, and rubbed his forehead: immediately the family mark disappeared, and the mark of the religious appeared in its place. He then, like an Elder of sixty years, fully dressed, carrying the eight necessary things, made a reverential obeisance to the royal Peacock, and walking around him right-wise, rose up in the air, and went away to the cavern on the peak of Mount Nanda. The peacock also, rising up from the snare, took his food and departed to the place in which he lived.

__________________________

The last stanza was repeated by the Master, telling how for seven years the hunter went about snare in hand, and was then set free from pain by the peacock king:

“The hunter traversed all the forest land

To catch the lord of peacocks, snare in hand.

The glorious lord of peacocks he set free

From pain, as soon as he was caught, like me.”

Having ended this discourse, the Master declared the Truths: now at the conclusion of the Truths, the backsliding Brother attained sainthood: then he identified the Birth by saying, “At that time I was the peacock king.”

Dedication

Roberta Mansell

…

Based on;

(Mahāmora-jātaka: tr. Cowell, E. B. (ed.). Chalmers, Robert, W. H. D. Rouse, H. T. Francis, R. A. Neil, E. B. Cowell (trans.). 1895–1907. The Jātaka or Stories of the Buddha's Former Births. 6 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. vol. IV)