Spirited Away: An environmental message about being a small player.

Subscribers contributions

At a time when societies are searching for the big ideas that will save the world, Adrian Mathews agues that the film Spirited Away may offer us a more local solution.

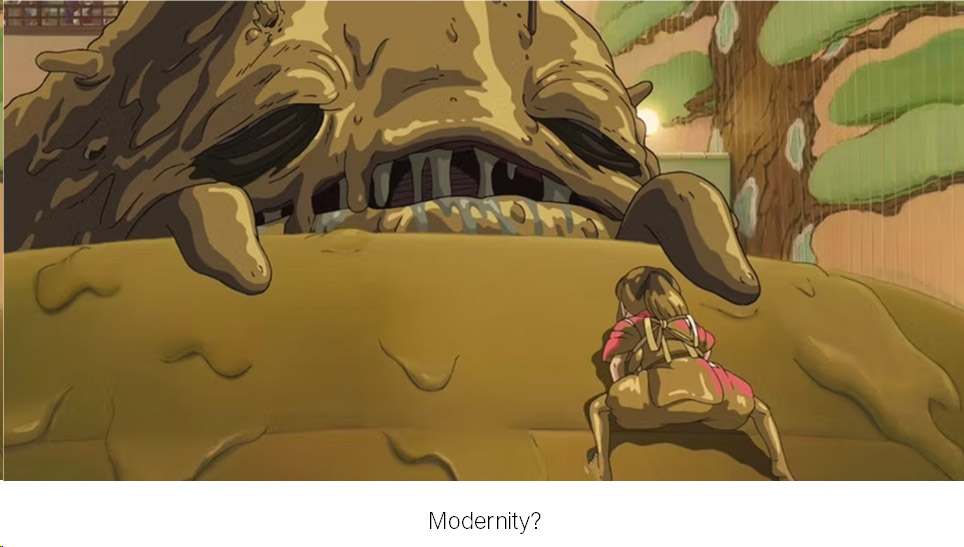

From the film Spirited Away

“Once you do something, you never forget. Even if you can't remember.”

I was speaking with a friend of mine last summer and the topic of the 2001 film Spirited Away, by Hayao Miyazaki, just happened to come into consciousness. It wasn’t a particularly convoluted discussion, rather it was a simple chat to see if both of us had seen the film and what we had thought of it.

It turned out that my friend, to my horror, had not understood why the film was ‘such a big thing’. A cardinal sin? No. But for those of us who adore Asian cinema it is perhaps the football equivalent of saying ‘Crystal Palace is a better team than Wigan’.

Recently, as I was preparing to write this article when another of my friends gave the exact same response. “Yeah, it’s pretty,” they said, over an admittedly watered down cup of coffee, “I just don’t get it, you know. Like, I know what happens. I can see how A leads to B, but, in a way, it feels like it’s a film where a bunch of stuff just happens. And that’s it. It’s incomprehensible”

I thought this topic of ‘incomprehensibility’ would be a good opening for this article. Think of it this way - how much of our lives is opaque to outsiders? Our personal interests can sometimes be incomprehensible to those around us. And it’s often a great joy when we find people who share in our unique perspectives. Yet, when we try to explain why something so niche is the greatest thing since triangle shaped tea bags, the best we can often hope for is a handful of like-minded souls, rarely do we get a crowd.

Nevertheless, my attempt here is not to make Spirited Away understandable to the general audience, as in itself it is a very simple story. However, what I do want to do, is to explain a single theme, that I contend refutes this notion of incomprehensibility.

But first, let me lay down the framework.

On the surface Spirited Away is quite a straightforward film. A young girl named Chihiro, is trapped in the spirit world because her parents eat a ‘forbidden fruit’ which transforms them into pigs (although in this case it’s a truckload of ramen which is the forbidden fruit, so I’m on team parents here). It should be noted that Chihiro moves heaven and earth to prevent this from happening, but sadly to no avail. As you can see from the image below, she’s not too happy about it.

The witch responsible for this series of calamitous events then offers Chihiro a chance to win back her parents’ freedom. To do this,she must first pay off her parents’ debt by working at a bathhouse for spirits, but in return for this job, Chihiro must first pay the price for giving up her name.

One thing to note here is that by selling her name Chihiro becomes almost like a spirit. It is still accepted that she is human, but, the longer she stays, the less humanlike she becomes and the more the human world begins to fade away.

But our plucky protagonist doesn’t let a bit of magic get in her way and ploughs on, vowing to save her parents. On the way, she discovers spiritual beings and helps these spirits, who are in need of succour and respite. And through the helpful aid of a dragon, the witch’s identical sister and a being called No Face, she succeeds in winning back her parents’ souls.

My sister calls it the Asian Alice in Wonderland and that’s quite a good comparison. It’s a fantastic story, but it occupies that strange liminal space where, purely from a literal perspective, one is not sure if any of it really happened at all. Did Alice dream of Wonderland, or did she actually go there. My view is both, but let’s leave that aside for now.

So, let’s first take a look at the film’s ecology before I get into the meat of this article.

Here we can see director Miyazaki-sensei’s love for the environment, but also the aesthetics of the traditional and modern Japan. The beauty of the bath house with its lacquered floors, red timber, paper sliding screens, is an odd prison for a young heroine. Indeed, apart from the food stalls where Chihiro’s parents feverishly consume food, hunched over, in their beast- skin guises, the world of Spirited Away is breathtakingly beautiful. And yet, our heroine is doing everything she can to leave it.

Odd, isn’t it?

It’s also important to note here that Miyazaki is a fervent anti-war campaigner and especially critical of some of the more lavish aspects of modernity. He is not, and has never claimed to be, a mystic or a scholar, but for an entire generation Miyazaki is emblematic of that wistful dream for the unreal. In this respect, there is little I can say except to admit to being in complete agreement with Miyazaki’s worldview. His love for the natural world spills over into his work, making each gust of wind feel ordained and every flutter of a shirt or skirt a certain kind of ‘real’ that is very difficult to express in words.

One of the more famous scenes in the film depicts a river spirit, disfigured into a form so toxic that its stench turns food sour and makes the eyes water. But this is a bathhouse and so Chihiro must clean the beast. It’s quite a process, and despite all the spirits of the bathhouse rushing to help clean the beast, in the end its left to Chihiro to do all the dirty work. Suddenly, there is an explosion of dirt. Plastic detritus and shopping trolleys spew from the beast, revealing the river spirit’s true form, a pure and wondrous spiritual being.

The environmental message is quite apparent here. It is the human world and our waste that has corrupted the spirit. However, pollution is not the same thing as climate change, and I would caution the audience from making the often-mistaken leap of reading this as a message about climate change. I believe, in fact, that it is a message more directly about consumption and, indeed, pollution. Whereas the latter is a complex issue, which is beyond my thesis to explore here, pollution is less a problem of burning too much carbon but more a reflection of our human excesses. Having just completed a big clear out after moving back in with my folks, that is a lesson I’ve learnt the hard way. Yet, as I watched the stink spirit scene again, it stirred in me a memory.

When I was in school, we had a short break between 10:30 and 10:45am. Our yard was about half a football pitch long and about two football pitches wide. The routine was simple. We’d all go outside, eat our snacks, deposit the left-overs and food wrappers on the concrete slabs and then return to class. As there were almost 500 of us, we caused such a mess that after we were safely enclosed for late morning lessons, a swarm of crows, seagulls, and a pretty mean looking hoard of several hundred sparrows, would all descend from the heavens and blacken out the school yard; it was a feast for them. Gazing out of the window, with a mind ill-tuned to learning French (or any language, including my native tongue, as a matter of fact), I would watch our lone caretaker wade through the murder of crows with a litter picker and black refuge bag.

Obviously, I felt guilty, even though I, like a good environmentalist, had put the crusts of my sandwiches into the bin. Annoyed too, given that of course we would all get the blame.

One could ask how, as a Buddhist, I should have responded. I could have gone around and cleaned up after the boys, but like Chihiro, I was chained to my chair having to request permission to leave it. If I had offered to clean the yard, I’d have met the usual, “Well, you know, your exams are the most important thing in your life right now.” I was part of a system that limited my ability to intervene. In retrospect, I wonder what sort of intervention would have been noble and right? How does one act when one is in a system that seems to perpetuate waste? Buddhism is a true and tested means of personal and transpersonal liberation, but can it, or should it, stop a group of teenagers from littering? Personally, I think “Yes”. But what I think Spirited Away is suggesting lies two or three steps back from the usual cadence of “There is no Earth 2.0”.

Think here of Chihiro. She knew that there is no such thing as a free lunch! Chihiro could see that human waste was turning the river spirit into a bloated mess and, remember, it is Chihiro’s parents who fell for the excesses of the food stalls, not Chihiro. Her parents make a beeline for the food which turns them into pigs, even while she tries to stop them.

Chihiro, in less than 10 minutes into the film, has realised the core error of over-consumption, and everything else is simply an act of clearing up her parents’ mess. But, as my father constantly reminds me, the problem with children is that they aren’t born with nappy changing skills. It’s learnt, usually later in life, with a lot of kicking and screaming.

Chihiro is no hero, and she doesn’t need to save the universe, just her parents. She is closer to you and I than she is to Superman, or Gandalf. Note that the cosmic scale of the universe is not changed by Chihiro saving her parents. The witch still runs the bathhouse at the final curtain call, a major distinction as opposed to say, Lord of the Rings. But Chihrio has done a little good. A small act of kindness.

So, back to the conversations I had with my two friends at the beginning of this article.

Spirited Away is incomprehensible because small acts of change don’t often get a lot of recognition. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t meaningful or comprehensible. In fact, I’d say they are more meaningful because “I” always want recognition.

Part of the confusion that my friends had voiced, I believe, is that we are primed to expect a grand narrative. We’re always looking for that technological fix that will turn carbon into cotton candy, and so we miss the small things that are not only more local but also more easily fixed. Another reason is, I suspect, that for a long time we have inflated our sense of agency in the world at the expense of others. By others I mean treating rivers, mountains, lakes, and even cities, not as things, but instead as beings worth being considered as part of a larger Earth Family. Think about your local hill, or stream, and how long it has been chugging along despite the shopping trollies and human waste clogging them up. Yes, it may now be a stink spirit, but I would contend that there are plenty of Chihiros out there just waiting for the bath house to open its doors.

For me, this has been a huge relief and extraordinarily helpful to the practice. By comparing myself to Chihiro and less to Frodo Baggins, for example, it has made dealing with the big issues less of a crisis on a global scale, as more of a local problem to which I can attend. I don’t have to bring a ring to Mordor. Wow, what a relief! This is truly my own personal belief, and I contend that Buddhism and environmentalism can only coexist when they deal with the “here and now,” with the local river and stream. At least for me, this is a manageable level of compassion.

I could go on further, but I would rather encourage you to go and watch the film for yourselves (or to go and see the stage play at the London Coliseum). This is not a story that you can truly ‘get’ unless you see it.

I’ll leave you all with this thought experiment. Throughout Spirited Away, Chihiro goes through a process of forgetting about the human world. In part, this is how the spirit world operates, but more significantly it reflects an understanding that by embedding yourself within an idea, a worldview, or a new perspective a whole new world can open up for you. So, given that I am writing for a primarily adult audience, I would encourage you all to forget yourselves as you watch. Think of it as a chance to be a 12- year- old again. Many would give up their right arm for that!

Spirited Away is available to stream as well as on DVD.

Also live on stage at the London Coliseum.

https://www.spiritedawayuk.com/

All images taken from, “Spirited Away.” Toho, 2001.