Martin Goodson

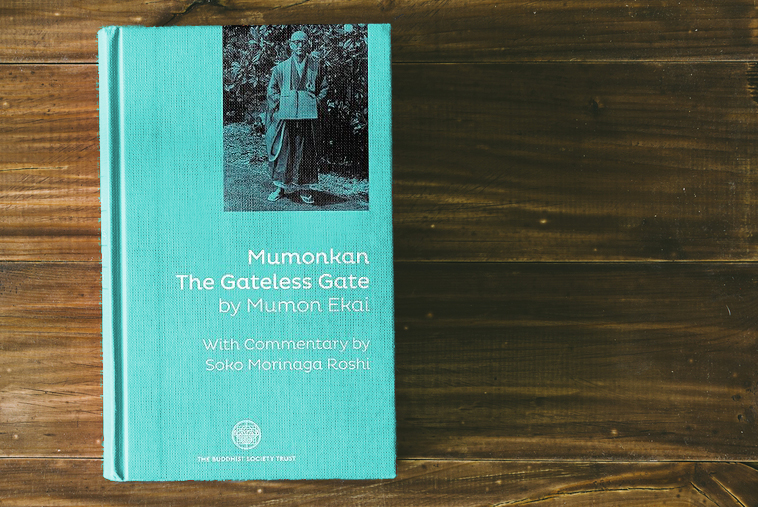

Mumonkan: The Gateless Gate by Mumon Ekai with commentary by Soko Morinaga Roshi

Book Review

Even before opening this book, I knew that this review would be whole-heartedly endorsing it and recommending it to our readership.

©

© shutterstock

Even before opening this 429- page book, published by The Buddhist Society of London, I knew that this review would be whole-heartedly endorsing it and recommending it to our readership.

Why?

Because, even though I had not read the book, I was already familiar with its contents. One reason was because of having read them serialised in Zen Traces, the in-house journal of The Zen Centre. The other reason was that I had the great good fortune to have been in attendance at the majority of the talks when they were originally given by Soko Morinaga Roshi (1925-1995) at The Buddhist Society’s Summer School during the 1980s and 1990s.

Since the death of Master Daiyu Myokyo in 2007, the Zen Centre and The Buddhist Society have been jointly publishing many of her writings that had languished for quite a while only in manuscript form or on floppy disk (yes you read that right - that’s how long they’ve been languishing!). As a result, a number of important works on Zen practice are now available for Westerners which help bridge the gap between Eastern systems of religion and practice and the Western mind, with its overweening attachment to ‘my’ individual self and its mind/body split.

One notable absence from this collection has been the series of teishos (talks given by a Zen master) given by Soko Morinaga Roshi on the 48 koans or ‘cases’ of Mumonkan (tr. The Gateless Gate).

Although not her own work, these talks from her mentor were instigated by Master Daiyu, so she could rightly claim to be a cause or condition of their creation.

Master Daiyu (or Dr Irmgard Schloegl, to use her pre-ordination name), got to know Soko Morinaga Roshi when she first went to the training monastery, Daitokuji, in the early 1960s. He was head monk at the time. Although her teacher was the abbot, Sesso Roshi, the abbot was a remote figure to his students, only being seen during teisho and interview (sanzen). For more day-to-day support, advice or to discuss a problem, students tend to go to the head monk.

But who was Soko Morinaga? These words, from the foreword by Dr Desmond Biddulph CBE, President of The Buddhist Society, tell us:

“In person, Soko was tall, warm and positive, quick and precise in his movements, but graceful and very natural at the same time. He was informal, but not in the least casual. His presence commanded respect but he didn’t demand it in any way. He was curious about all things English: oak trees, stately homes, the punk movement. Our history, geopolitics (some of it to the dismay of our own teacher) as an Island people close to a continent seemed to parallel Japan with its proximity to Korea, China, and Asia; the politeness such as there was here, he enjoyed, as well as English customs and our monarchy.

… There was nothing slow or ponderous about him, on the contrary he seemed animated by a dynamic energy that touched us all, in some way. Many who attended his Teishos were deeply moved, others inspired, few were unaffected. He seemed to us young students of Zen the embodiment of everything a Zen Master should be.”

What of Mumon, the author of the original text on which Soko based his commentaries? His Chinese name is Wumen Huikai (1183-1260). A Chan/Zen master of the Song period in China, The Gateless Gate is his most famous legacy to the world of Zen and Chinese religious literature. Made up of 48 koans with short comment and a verse composed by Mumon, this collection contains some of the most famous koans known to many.

Who hasn’t heard about the monk who asks Master Joshu if a dog has Buddha nature? Joshu replies “MU” meaning “No!” - an apparent direct contradiction to the Buddha’s exclamation that “All beings have the Buddha nature”, which he declared upon his own awakening under the Bodhi Tree, according to the Northern tradition.

There is also the ‘origin’ story of the Zen tradition itself when, late in his life, the Buddha was to give a sermon to a large assembly. Sitting silently, the crowd leaning forward in anticipation, the Buddha lifted up a flower and Mahakasyapa smiled. The Buddha seeing this gave the transmission of the eye of the Dharma to him.

There is also the startling story of Master Nansen who kills a cat! Tozan’s sixty blows and Ummon’s shit-stick.

The gift that Soko gave to us in his teishos, all those years ago, was to take the sparse one or two sentences of the koan and not only paint a landscape but to bring it to full life right before our eyes. It is difficult to describe his method, let alone its effect on the consciousness of his hearers, since I cannot think of another experience quite like it: perhaps great art or music in its power to evoke something mysterious into conscious awareness. There are stories form the Mahayana sutras where the Buddha, though his miraculous powers, enables his audiences to see before them the billion-world universes each with its own living Buddha radiating light in myriad ways in order to bring delight and wonder as inspiration to continue along the Way.

Perhaps an excerpt might bring something over: this from the first koan of the collection, the aforesaid case of Joshu’s MU:

The Verse

“The dog - Buddha-nature!

Quite at ease and with true authority.

But if you become involved in ‘yes’ and ‘no’, however little,

You lose both body and life”.

Soko Roshi’s Comments:

“For listening to teisho, both body and heart need to be relaxed, ready and open to receive. When a cup is full, or the heart is filled, there is no room for anything new to enter.

I became a monk because I had lost the sense of any purpose to my life and was spiritually drifting. Since then, forty years have passed. As I see it, these days sadness, grief and pain have by no means disappeared. Every day brings both happiness and pain; however, they are not problems. If you look out at the landscape, there is no problem; there are just trees, grass, clouds. Yet people create problems out of these, like it is cloudy, or that trees are growing too close, or perhaps even the fact that grass is too green! In a letter I recently received, the writer said that he could not grasp how Buddha-nature can be inherent in trees or grass. Why? If trees or grass or a desk are endowed with Buddha-nature, why is it that these, unlike human beings, unlike the writer himself, do not feel anguish?

My answer to the person looking at the trees, at the grass, or at the desk, would be that if they really want to make a problem out of it, this is the way to do it: not to wonder why trees, etc., do not feel pain or anguish, but rather to ask why it is that I, endowed with the same Buddha-nature as they have - why is it that I feel anguish?… This same mistake is what our koan today is concerned with.”

To be honest, it would not be hard to write a much longer screed on why you should get this book, but I’d much rather you just read this book!

The Zen Centre, The Buddhist Society, Dr Desmond Biddulph and the editors, Eifion Thomas and Michelle Bromley, should be commended for bringing this book into existence.